Working the door at the New Penelope with Allan Youster

Allan Youster has been a mainstay in the audience at local concerts for decades in Montreal. He spent part of the late 1960s working the door at legendary local concert venue The New Penelope Café, witnessing performances by such figures as Muddy Waters, The Fugs, Jesse Winchester and Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. Louis Rastelli spoke to him for this project at one of his favourite local haunts, Barfly, in the summer of 2015, and followed up a few months later at his longtime home in the Milton-Parc co-op in the fall of 2015. (He was also interviewed HERE for an oral history of the Milton-Parc housing battles of the 1970s). The interviews were transcribed and edited by Alex Taylor and Louis Rastelli, with graphics provided by Erik Slutsky, Alex Taylor and others.

LR: Were you born and raised in Montreal?

AY: I was born just over there on Coloniale (near Duluth). Then my parents moved up to St-Joseph Boulevard, then we moved again with the big Jewish migration west. We only made it as far as the cheap apartments in St-Laurent. Some of our family ended up in Chomedey and other places. My mother was from Glasgow, but my father was a Montreal Jew. He lied about his age at 17 and went off to fight in World War II. Even though the war ended in 45, it took over a year to get back home. My mother was a war bride, she had come over then too. So I was born in 1947. I went to Sir Winston Churchill High School in the early 1960s.

LR: Ville Saint-Laurent was brand new then, wasn’t it?

AY: I went to Sir Winston in its first year! It was on the edge of Cote-Vertu; behind the school was all fields. West of Alexis Nihon, Cote-Vertu was a two-lane country road like Gouin Boulevard, there were only farms and stables out there. I remember one day, the school shook — Canadair (the airplane manufacturer on Thimens, now Bombardier) was a little ways over east, then Dorval Airport was just west of us. They had a runway number 7 at Dorval, and a runway number 7 at Canadair. So a passenger plane coming in had mistaken which runway, and came in so low that the vibrations shook the whole school. It made the papers – they ended up closing that runway at Canadair after that.

LR: They don’t test their planes there anymore …

AY: No, no. It’s amazing what’s there now; they’ve just built and built. Actually the first show I ever saw was back in Ville St-Laurent, at the Y, I saw Penny Lang there. She had a bass player with her and sang cover tunes. I think the building is still there.

LR: By coincidence, I went to kindergarten at that Y, up near Poirier.

AY: Yeah, up there. We had a teacher in high school who started a folk music club. That was where I first heard Bob Dylan, she played the first album for us. Phil Ochs, all this before the Beatles, maybe 61, 62.

When we were in the Folk Song Club, we were the only ones who cared about that music, and we were just a bunch of nerds. It wasn’t popular at all. You have to understand, Dylan’s only single was Tambourine Man. It was slow and 6 minutes long, so it got played at all the high school dances. This was way before Stairway to Heaven. But he wasn’t all that popular.

The Beatles for me, were a real watershed. I discovered The Beatles in November of ‘63, before they were famous in February of ’64 from Ed Sullivan. We’re Jewish and Chanukah was coming up at the end of November and my mother says, “You have to buy your sister a gift.” I have no money, so she gives me five dollars. We’re at a record store, I see the Meet The Beatles LP, wrap it up and give it to my sister Rena. She doesn’t like it! She gives it back. I can’t believe it! I Love it!

Now we’re living in a duplex, so we do our stuff with the family and then it’s over. Afterwards, I run downstairs to my neighbours and say: “You gotta hear this!”

We put it on down there in the basement, and they called their friends, so before you know it we had about eight people listening to The Beatles going “This is incredible!” I even took it to school that December, and our history teacher who was from Scotland— Miss Chesney— she said: “Oh! I see you’ve discovered the British stuff… I was there this summer and I have all these 45s I bought.” So we had a sock-hop in our gym where I brought my record and she brought in hers… everybody took their shoes off and were dancing in the gym. We’re part of the British Empire… British stuff gets released here and just shows up in the stores whereas in the States, it took longer to come out. So by the time February comes, we were stoked for the Ed Sullivan show!!

LR: But why did it sound different? Had you really not ever heard Chuck Berry or any Motown by then? Songs like the original “Twist & Shout”?

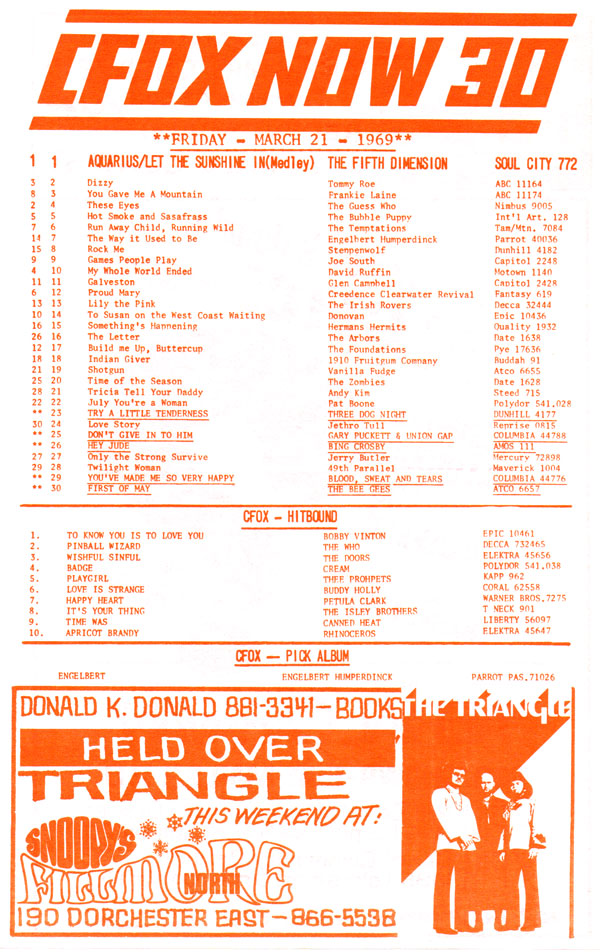

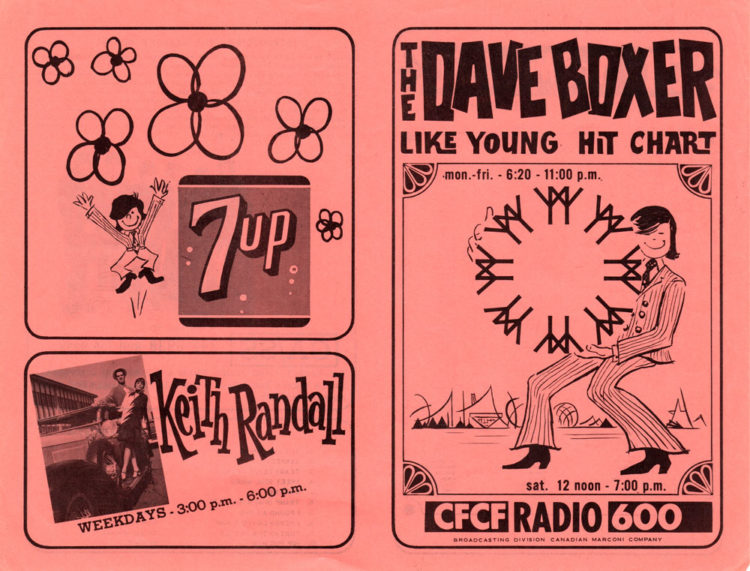

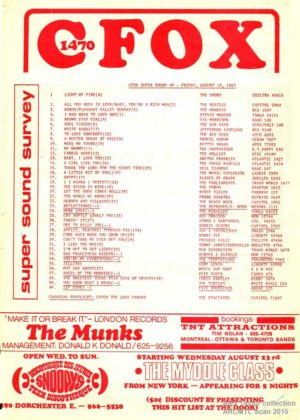

AY: You have to understand that you can’t throw the black charts at us. We were still at the end of the black “race records” era. We had Dean Hagopian. Dean was the big CFOX adversary of Dave Boxer at CFCF. Dave Boxer was the most popular, but Dean Hagopian was the most hip, because he was playing the black groups, RnB, the older stuff and the stuff not playing on the white charts. So we knew about that stuff, but it was not popular. But the Beatles arrived at the right time, in the right spot, with the right harmonies, and it just struck a chord. The first song I ever heard was “It Won’t Be Long”… that was like church music call & reply. It captured me at the time… it captured everybody, it was amazing! At this point, you can’t find other records like that. My mother’s from Scotland, so we wrote to our relatives there to send us more Beatles stuff.

LR: It must have been like such a breath of fresh air?

AY: Yeah! It was somehow releasing. All of us, after that whole thing hit, everybody was going, ‘Hey! I can do that!” Later on, we got to hear all that other stuff. The British bluesmen re-introduced America to its own music.

So my mother’s relatives sent us more Beatles and other stuff from Scotland. The day I got the first album, a friend of mine, Larry Geary, knocked on my door at 8:15 in the morning before school, and he had a new record… Paul Butterfield’s first album with “Born in Chicago” on it. Anyways, he says: “You gotta hear this” and we put it on and my mother came in and said: “Why is it so loud?” and I said: “Mom, it says on the back of the cover—Play as Loud as you can!” (laughs). We were open to all that, listening to Butterfield, The Beatles & The Stones, Muddy…

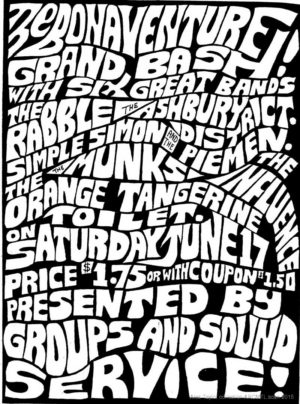

In high school, the pop bands that I liked were bands like JB and the Playboys. I got their albums, their 45s… I’d also see them and bands like the Haunted and MG & the Escorts at the Bonaventure Curling Club. We had a friend with a car and we would go out there. It was in an industrial park, but before the big highway was built. In the summer, they had 5 or 6 thousand kids in there. They would bring in 10 bands, one after the other. They would all get 20 minutes, half an hour and as you were a bigger name, you would get more time. The sound was terrible, the sound was cavernous! but the sound was terrible everywhere then. But it was an EVENT. It was Rock’n’Roll. People would buy a mickey of rum and sneak it in and you could buy a Coke there. It was like a high school gym, but at an industrial level.

In high school, the pop bands that I liked were bands like JB and the Playboys. I got their albums, their 45s… I’d also see them and bands like the Haunted and MG & the Escorts at the Bonaventure Curling Club. We had a friend with a car and we would go out there. It was in an industrial park, but before the big highway was built. In the summer, they had 5 or 6 thousand kids in there. They would bring in 10 bands, one after the other. They would all get 20 minutes, half an hour and as you were a bigger name, you would get more time. The sound was terrible, the sound was cavernous! but the sound was terrible everywhere then. But it was an EVENT. It was Rock’n’Roll. People would buy a mickey of rum and sneak it in and you could buy a Coke there. It was like a high school gym, but at an industrial level.

I remember a group called The Munks, they covered The Zombies’ “She’s Not There” before we heard it on the radio. But nothing stands out in memory more than THE CROWD! It was the teenage crowd, the parking lot, people looking for teenage girls, girls looking for boys, girls looking for trouble, alcohol—no drugs—if there were drugs, it was so low key we didn’t pick up on it. It was really high school on an octane level, a sock hop with alcohol. And the high school dances had bands, Winston Churchill had bands. Bands were localized, back then, a band could be local for a high school, and a few blocks away, nobody knew them. The local scene was really funny. And Donald K. Donald. I actually remember him at the Bonaventure with one of those folding wood tables, with two turntables, a Bogen amp and two speakers. He was playing the music and was getting local bands to play at high schools, and that’s how he started.

LR: He picked up bands like The Triangle…

AY: Yeah! Actually, at one point he even got some of the bands that played at The Penelope to play some of the high schools, because he was already hooked up.

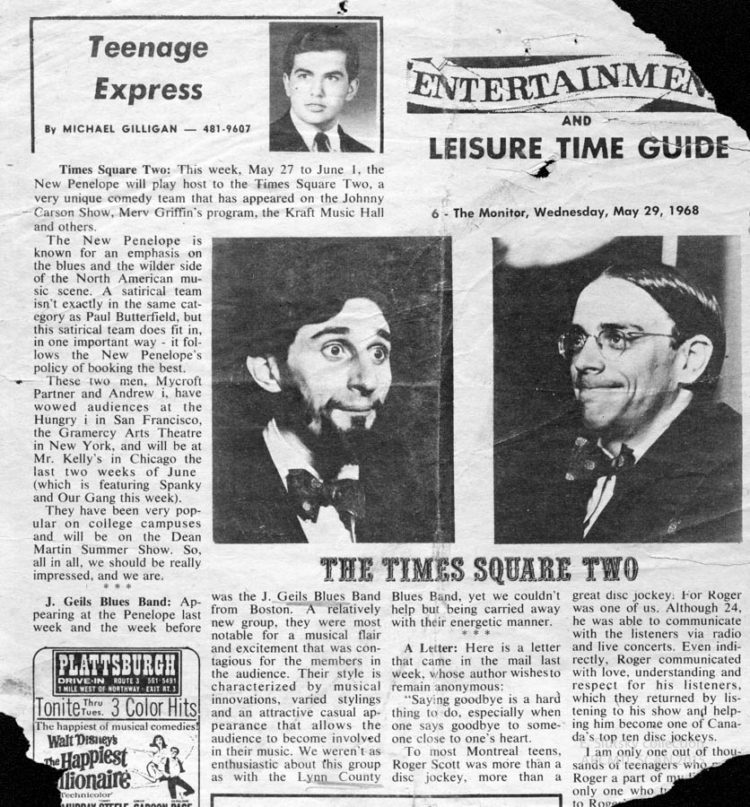

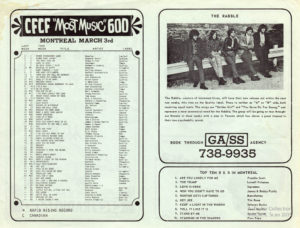

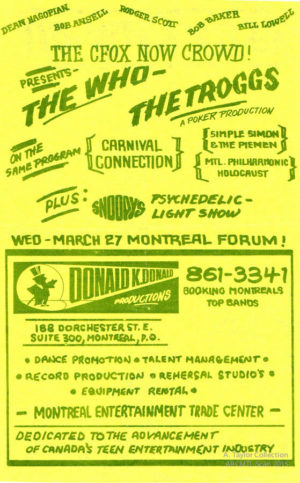

A flyer that was typically free to pick up at record stores in the 1960s. From the collection of Alex Taylor.

LR: There seemed to be a brief point after The Beatles hit where a lot of the gigs at the Bonaventure or Maurice Richard Arena had a mix of French yé-yé bands & English bands like The Haunted or The Rabble…

AY: OK, well Les Classels & Les Baronets, I remember them, but I wouldn’t listen to them because, basically, that was pop crap! I mean now, it’s elevated to a place of nostalgia, but at the time — remember I said that the music was divided? – well, that was pop crap!

LR: There were others that crossed over more, maybe Les Sultans or Sinners?

AY: The Sinners, definitely! Sultans, yeah, they were moving in that direction. The one song that did it for them was “La Poupee Qui Fait Non” – that’s the stupidest song but it went to #1.

LR: I can’t help but think that these days, three years go by, and it’s not like the whole world changes. In those days, in ’64, The Beatles exploded, then by 1967 you’ve got acid-rock… it’s like the whole world changed in three years! Think of 2012’s music compared to 2015’s for example and it’s more or less the same. Did it feel as fast-paced as it seems now?

AY: Well at the time, we were listening to jazz, to folk, to rock and popular music as well. This was slightly before CKGM-FM, but there’s other stuff that’s not on the radio that we’re listening to as well. When the British stuff hit, everybody was listening to the British stuff, but not everybody was listening to Bob Dylan, to the Butterfield Blues Band or following all of “our stuff.” So there were two or three streams of popular music at the time.

For Montreal, the really big change was CKGM-FM, that was Geoff Sterling who bought that radio station. I mean, there really hasn’t been radio like that since. Even CKUT today doesn’t do that. Two years in a row, they won the best radio station in North America, picked by Rolling Stone… Geoff Sterling just let the DJs do what they want. You could turn it on, hear Hendrix followed by Ravi Shankar followed by John Coltrane… playing one long cut of each. There was nothing these people wouldn’t do! It was music, it was just “out there!” Nobody is that free-form today… Meatball Fulton was one of the deejays… free-form, but within the politics of the station…

LR: You were lucky to live in St-Laurent then, not far from the Bonaventure. It must have been quite a commute if you wanted to go downtown.

AY: Well… Here’s a personal story, I was tall for my age then, five foot eight and a half, same as I am now since I was twelve or thirteen. Then at thirteen, they gave you a suit, for bar mitzvah. So to do anything back then, you had to be over sixteen. There had been that stampede in a theatre in the 20s (Laurier Theatre fire), even when I was a kid, you couldn’t go to the movies. But I realized, if I wore my suit, I could go to the movies. So I was going downtown after school, I’d go see movies, hockey games. Standing room at the Montreal Forum was a dollar. I’d tell my mom, “Going to school,” then go in the morning to the Forum, stand in line, pay a dollar for standing room. Get back on the bus with the transfer, back to school a bit late. I have to admit, my father passed away when I was quite young and I would get a lot of mileage out of that too.

Then at night I’d go down and watch the hockey game. In high school, I had this thing where I was tall, remember, I looked older. I could get into strip clubs – my favourite one was one called the Metropole. It was across from Eaton’s. You won’t believe this, but they had live musicians, sax, bass and drums. They would play what you might call bedroom sax, and they were competent jazz musicians. I had discovered jazz, blues along with folk at the Record Centre on Crescent. There’s a falafel place there now. That was Edgar Jones’ shop, you could rent a record for 25 cents a week. There would always be college kids and stuff hanging around, so I’d start hearing about things, and I find out about the Penelope Café, on Stanley. That was next to the Stanley Pub, downstairs.

Then at night I’d go down and watch the hockey game. In high school, I had this thing where I was tall, remember, I looked older. I could get into strip clubs – my favourite one was one called the Metropole. It was across from Eaton’s. You won’t believe this, but they had live musicians, sax, bass and drums. They would play what you might call bedroom sax, and they were competent jazz musicians. I had discovered jazz, blues along with folk at the Record Centre on Crescent. There’s a falafel place there now. That was Edgar Jones’ shop, you could rent a record for 25 cents a week. There would always be college kids and stuff hanging around, so I’d start hearing about things, and I find out about the Penelope Café, on Stanley. That was next to the Stanley Pub, downstairs.

Upstairs was the Loon Rousse, a nightclub. I remember one time coming out of the Penelope late at night, and in front of the Loon Rousse a big Cadillac type car rolls up, four guys come out, they open the trunk and take out baseball bats and run into the place. My friend looks at me and says, I don’t think a baseball game is breaking out in there. We got out of there. That was the Loon Rousse for you.

The Penelope on Stanley was very small. It was a folk club, you sat around wooden barrels, with plywood on it and a checkered tablecloth, on old tavern chairs. If you fit fifty people in there, there’d be no room to stand. My favourite bands I saw there were Luke and the Apostles, from Toronto, Sidetrack, and various folk acts. Sean Gagné, Willie Dunn, all the local folk singers played there. Willie Dunn was the first guy I ever did see play slide guitar with a knife. He was playing guitar, but I didn’t realize he was carrying a knife… I mean, I’ve seen a glass, a bottle, but the knife …after playing, he’d put it back in the sheath and that was that! (laughs)

Gary Eisenkraft had a story about Bob Dylan, he said Shimon Ashe refused Bob Dylan at his folk club. Dylan went in on open mic night and did a set, the recording is out there (Finjan’s 1962.) A couple of months later, Shimon gets a call, saying Bob Dylan was going to be in town. He could come to Montreal for a week, the price would be $800. Shimon is just about to go bankrupt, he says to Bob, “Sorry, I can’t.” So after Bob Dylan became famous, Shimon’s story became, “I turned Bob Dylan down.” How many people can say that?

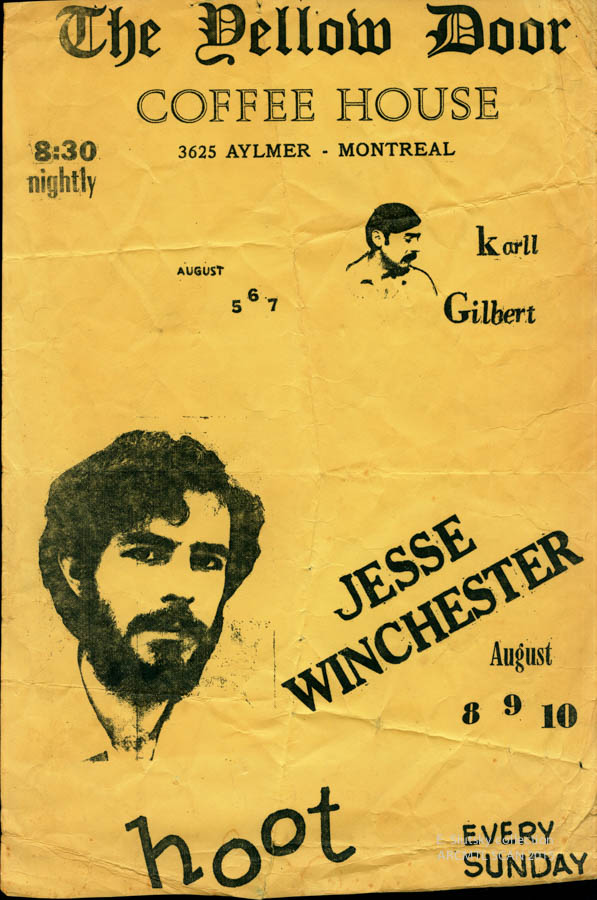

The folk song clubs didn’t work for that long. You do have the Yellow Door, but it was part of the campus. The Green Lantern, the Back Door in the early 70s on MacTavish and Sherbrooke, you literally had to go around to the back door of the building, it was in the Prince of Wales Court at McGill, which was later demolished. I saw the Reverend Blind Gary Davis there, on my wedding night in 1970. Saw Bruce Cockburn there at least two or three times.

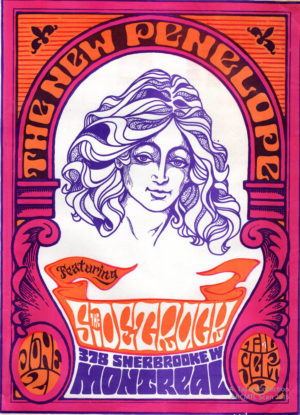

When the Penelope moved to Sherbrooke St. in 67 (and became the New Penelope), it was exciting. The old place was small—when Sidetrack played there, they were six people, and they had two keyboards, one of them was a harpsichord. There wasn’t a lot of room in there. I was unemployed. I was exactly 20 in ’67. The Penelope had moved to the new place and needed staff, so I said “I’ll work there.” I was paid six dollars a week to do the door– a dollar a day.

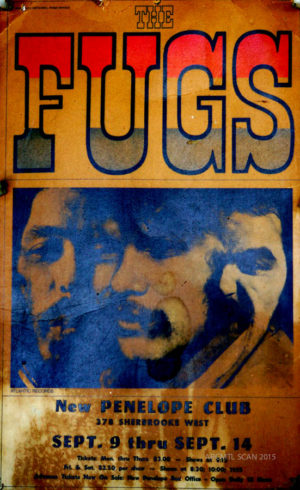

Gary liked me because I’m anal and I worked the door honestly. People would offer me drugs, girls would offer me drugs and more, but in the end, everybody paid to get in. That’s why Gary liked me– it was a business. Paying $2.75 was a big deal, this was for something like The Fugs… it was the top show.

I worked 6 days a week, because we were closed on Mondays. But I was collecting unemployment insurance, $27 a week, I got $54 every 2 weeks. So with the $6 I earned at The Penelope I lived like a king– well OK, a poor king! But I got to see the shows for free.

I worked 6 days a week, because we were closed on Mondays. But I was collecting unemployment insurance, $27 a week, I got $54 every 2 weeks. So with the $6 I earned at The Penelope I lived like a king– well OK, a poor king! But I got to see the shows for free.

Usually we’d stop charging in the middle of the second set. Most bands would play two sets, Friday & Saturday they played three sets and could go on past 1 am. I remember Muddy Waters, three sets for Muddy, and it was crowded, I mean 526 people there for his first set, those were the tickets sold – not including the band and their people, and the two cops who got in for free. I remember the cops drove up, they parked their car after the opening act, and I was at the door and they came in just to watch Muddy. Two cops standing in the back. I mean our capacity for the place, officially, was 155.

LR: Well Sala Rossa is similar, the official capacity is 200 but you can get 500 in for the big shows. Was it the same sort of size as Sala?

AY: No, smaller, we’re talking jam-packed– we had a vestibule too so some people were in there, and Muddy was basically in another room, but it was a small place. The stage was no more than a foot or foot and a half high. There was no sign out front, it was only on the door.

Sidetrack were great, they were the New Penelope’s house band. Now in New York, at the Café a Go Go, the house band was the Paul Butterfield Blues Band for six months, then Sidetrack took over. They were that good! Sidetrack were more like Butterfield on the first album, harmonica, straight blues, plus a jazzy component. The keyboard guy played an electric piano (Rhodes type) and the other guy played a homemade harpsichord. Their theme song went, “Let me be your side track — until your mainline comes.” There was J.C. Lewis, short, curly hair, wore round sunglasses like John Lennon, played harmonica, great voice, drove a stripped-down BMW, wore leather. Died of throat cancer really, really young. The drummer was from Miami. The core of the band was from Montreal.

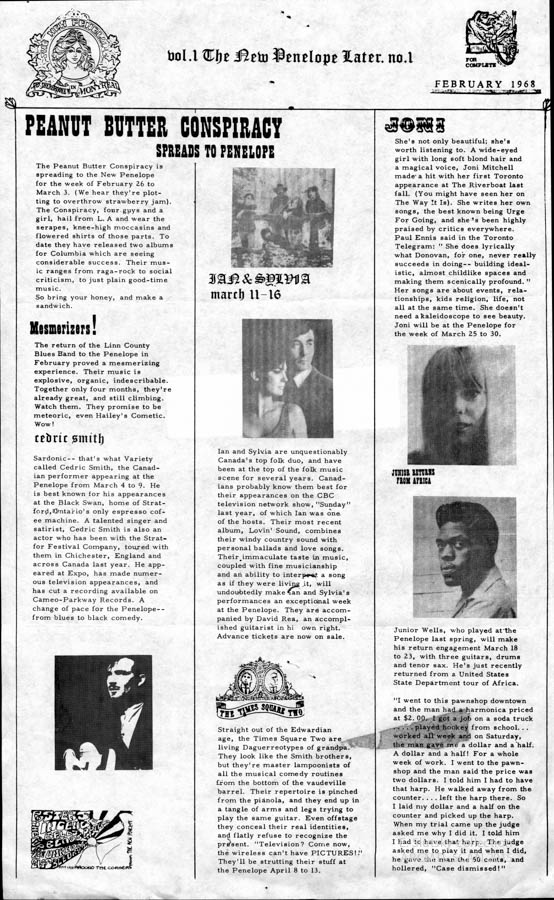

The other house band at the Penelope was Jesse Winchester. I was lucky to be there, he comes in with his guitar case, Gary’s there. It was an audition. He gets up on stage, he has his nice white Fender reverb amp, he does Yankee Lady, Black Dog, and I forget the third song. Gary recognized a songwriter, and on his electric guitar he had the tremolo turned up high for “Black Dog” with that spooky thing. Gary says to him, “Anytime nobody’s playing here, you’re playing here. Anytime somebody’s playing here, you’re opening.” Jesse later got hooked up with the guys from The Band. Every time he played there, he did another new song he wrote. He would write new songs all the time. He was one of those guys who—every time he came in—he would say: “I have a new song.”

I saw Muddy at the New Penelope twice, Butterfield played twice, James Cotton played twice. Muddy… what a gentleman that guy was, and James Cotton, what a fun guy! The first time he came, he had Otis Spann on piano which was just incredible! Whenever James Cotton came up, he always brought a pound of grass, but would never take it back with him. Coming into Canada was a breeze, but leaving, you could never bring it back in.

I saw Muddy at the New Penelope twice, Butterfield played twice, James Cotton played twice. Muddy… what a gentleman that guy was, and James Cotton, what a fun guy! The first time he came, he had Otis Spann on piano which was just incredible! Whenever James Cotton came up, he always brought a pound of grass, but would never take it back with him. Coming into Canada was a breeze, but leaving, you could never bring it back in.

LR: How much of the pound would he smoke? That’s a lot of weed!

AY: They would come with a pound and be stoned all the time, be as happy as could be, and before he went back—they would just give it away to who was left… whoever was hanging around at the Penelope. You couldn’t smoke pot inside the New Penelope. Gary would put up with none of that! Everybody went out, around the corner, but not inside the club. He was very nervous about that.

LR: What about that little field on the corner, Bleury Beach—could you smoke there?

AY: We’d go to Sherbrooke, at the bottom of Hutchinson. Right now there’s two hotels there. There used to be a section of low, two or three storey buildings there. Next to it was the Swiss Hut, and then the Country Palace, which we called the “Cow Palace”. Those were actually all owned by the same person and run off the same liquor license, because they had an adjoining door, but the Swiss Hut was hippie-dippies-motorcycle-druggies, and the other one was Country music… two different cultures so close together… and they didn’t like the hippie-dips!

LR: That was an old cliché you see in Easy Rider, with the “good old boys” trying to beat up the hippies.

AY: It wasn’t a cliché there. They tolerated us next door and around, but not inside the Country Palace: It wasn’t the place to be. It was visibly hostile and physically hostile. It wasn’t nice! I had long hair, a beard and you would go on a bus and sit down and people would move away from you… but it was OK, I didn’t feel bad. I would actually move over and sit and see how far I could get people to move. It was just weird!

LR: So, the Swiss Hut was where between sets or even during a set at the Penelope, if you wanted to drink during a show, you would go over and order beers and then go and walk back in…

AY: Well, there would always be the fifteen minute break between sets, which was actually 45 minutes, some people would go out and have a cigarette, go in for a drink—they would chug them.

LR: You could have a smoke at the New Penelope though?

AY: Yeah, you could smoke… I’d forgotten that there were ashtrays that I had to clean… you could smoke inside, but not pot.

LR: So what about the musicians? Did they have a basement, back room or backstage?

AY: No. When you came in, there was a vestibule, there was a ticket booth, some other room and then there was a large, one-room dressing room, and that was it. So, they could have smoked in there, but if you were outside, there was a parking lot behind the place. So if you were there, you can walk out the back door or go to the bathroom and smoke but, people in there had to go outside and walk around. Pot wasn’t as it is now. It was so new, I mean it was pretty loose, but back then it was weird!

A frame from an undeveloped negative taken at the then-new New Penelope on Sherbrooke St. in 1967 by Jeremy Taylor, from the collection of Francois Dallegret, digitized by ARCMTL in 2015.

LR: So, you didn’t worry that the cops would put you in jail for life?

AY: When you walked through the McGill ghetto, or you walked through that whole area, it was more student oriented than it is now. I mean, it was just open door parties. Nobody locked their doors. When I grew up and went to high school, I never had a key to the house, we just didn’t lock the doors. We lived in St-Laurent until I left, in ’75, and we didn’t lock the doors. It was quite open, but Gary wouldn’t allow pot inside the Penelope, which was gonna draw heat. I’m sure they tried to get a liquor license, but were just told “NO”.

LR: Do you remember many francophones going to shows or playing at the New Penelope?

AY: Robert Charlebois played at the New Penelope [with backing band LE QUATUOR JAZZ LIBRE DU QUEBEC], they played two Sundays in a row. Bands would play Tuesday to Saturday, we had a local band on Sunday and Monday we were closed. That would be the schedule. Sunday was a slow night, only two sets. Sonny Greenwich played there a couple of Sundays, but anyways, back to Louise Forestier & Robert Charlebois.

LR: Were they the only French act to play at the New Penelope?

AY: Yeah!

LR: Did people show up for Charlebois?

AY: Oh yeah! But put it this way, it wasn’t the regulars – they brought in their own crowd. I saw them and I couldn’t believe it! They were amazing! Then I saw them the next Sunday and then I got it – the chansonnier thing – everything was the same, every hand gesture, every emotion, every facial gesture was the same! I didn’t really realize that before. One of the things about the Penelope was you could see a band play there for a week straight… Muddy Waters’ band, they never played the same song twice… they played the same song, but the guitar solos were different….

LR: So when he played five nights in a row, three sets in a night….

AY: He would do Tuesday-Wednesday-Thursday two sets, Friday-Saturday three sets, play a lot of the same songs, but the guitar solos weren’t the same. That was the beauty of the stuff. With the chansonniers, every hand gesture was repeated. There were bands that were “acts,” like the Times Square Two, they were a folk act and had a shtick, skits, but it was exactly the same and you would know what was coming.

LR: Did you go to the Esquire Show Bar for shows?

LR: Did you go to the Esquire Show Bar for shows?

AY: I went more when Gary went there. It was a little weird at the end. It was a place where you had to buy a drink for each set, it was a little high-end… it was more expensive and not as relaxed, but the Penelope was something special, definitely a coffeehouse.

LR: It’s hard to image today that there was just one club like that…

AY: If the Penelope had had a liquor license it might still be around today. It’s one of the reasons I personally hang out at the Barfly, it’s not for the beer, it’s for the music and the people… it’s above and beyond the place itself!

LR: Going back to the old days, where did you go in St-Laurent to buy a record then?

AY: Jay Boivin was in the Sinners, and his parents had a record store on Decarie near du College, right across from the Boucher de France and next to Beaudet park, called Boivin’s that sold musical instruments and records.

LR: There was a music store nearby there where I used to go buy guitar strings …

AY: B-Sharp. They sold instruments and later became a rental place, and bands would come in and rent equipment. Bob Panetta worked there, I think he was in The Oven (St-Laurent rock band). He has a Zappa story—He actually lent Zappa his amplifier, because Zappa went down to B-Sharp to rent and there was nothing there—everything was out.

At first it was on Decarie and then it moved around the corner onto MacDonald Street, where it had a basement and was a much bigger store. That’s actually where I met my wife Gail—Bob Panetta introduced me. I went over to B-Sharp one day to see Bob and he went out on break time, and said let me introduce you …

LR: Did you know the owner, Jack Tepley?

AY: Sure! Here [Goes to the other room to show promotional poster for the album Abbey Road], this is from Tepley. When it came out, it was in his store for years. When we were getting married, he went: “I’ll give you a gift. What would you like? Don’t ask for too much!” and I went: “How about that poster? When you’re done with it” and he said: “Sure, sure, a wedding gift!” Later he dropped all the music stuff and just went into renting equipment. Do you know how it worked in there? When you went, he took your picture. He had pictures of everybody who rented his equipment. Bands would come in to rent a piece of equipment… “I never rented it!” and he would say: “You’re standing with it and I took a picture.” Because he had gotten ripped-off so many times. He got out of all that, and just went into renting. He rented sound systems, stages—he was big—for a while.

LR: We haven’t talked about Expo… I heard that Expo 67 almost killed downtown because everybody split to go there…

AY: Oh yeah! The New Penelope didn’t open until Expo closed. If you had your passport, you got in free at Expo 67 everyday, but if there was a show, you had to pay. There were a lot of bands playing at Expo all the time, local bands… friends of ours from St-Laurent… Sheffield Steel played at Expo, they hired all kinds of bands.

At the New Penelope The Sidetrack were the house band all summer. They were doing strict blues with extended solos and they would have the piano… they had great soloists and that was the thing back then, [like Paul Butterfield’s Blues Band LP] East-West. That was happening live everywhere, bands just got into a groove and jammed. Later on Sidetrack went to New York and they made them the most god-awful album.

Anyway, back to the old Penelope: I was just going there and hanging around so much that I knew everybody, so when the New Penelope opened and I was willing to work for $6 a week… as much as I loved Gary, he was never known for being a philanthropist.

LR: So he was a co-owner?

AY: He was the name. There were three: Nat Katz, Bob McKenzie & Gary Eisenkraft, but Gary was the manager, he was the name and he was the connection, he knew Albert Grossman in New York and that’s how he got Butterfield, the Fugs… I think Nat was an engineer and had a job but I didn’t see him very much, he didn’t involve himself much with the place, he’d come once in a while. Gary was the front man, but Bob was there too and would introduce acts when Gary wasn’t around, and he was there quite a bit. He lived near the place.

LR: From what we’ve heard, it seams that Gary did just about everything: book the place, pick the bands, write the contracts and I’m assuming he had to buy the material, hire & fire personnel…

AY: There were waitresses there, always two or three. On the busy nights there was three. You’re only making money selling coffee and hot chocolate, lemonade and orange juice and you have 200-300 people in there and they’re thirsty, that’s where you’re making your money. The tickets are going to pay the band—you gotta pay the rent and pay yourself!

LR: But I’m sure he was able to take a cut, like I see The Fugs, two shows a night, five nights in a row, $2.50. Let’s say that there’s 200 at each show…

AY: Oh! I would say more than 200 per show.

An original copy of the cardstock Fugs poster that hung at the New Penelope before their 1967 show. Allan Youster put it up on his wall just after the show, where it remained until ARCMTL briefly removed it for digitization in 2015.

LR: Well, that’s over a grand a night! I don’t think the Fugs were pocketing a grand a night. I’m sure they were happy with $500-600 a show.

AY: They were like The Beastie Boys—they didn’t play—there was a band behind them. They were out in front, doing their schtick, they were the singers. They had a bass-guitar-drum, a great rock band—we’re talking New York fuckin’ musicians! This was after Virgin Fugs [LP], Tenderness Junction was the album at the time, so it was that band [playing].

LR: Somebody told us that they actually remember how one of the shows started—I think it was Ed Sanders who came out and started “What to do in case of an atomic bomb,” which was one of their set-pieces… it ends with “put your head between your legs and kiss your ass goodbye!”

AY: I have a prop from back then. It just says: “Ho Chi Min Trail” with an arrow. When they left, I came in—and I guess no one cleaned up and it was laying there on the floor and they were gone. I picked it up and took it home. It doesn’t say Fugs on it or anything, just a homemade Ho Chi Min Trail with an arrow. They played there twice, each time was for one week.

LR: You must have not missed many shows at the Penelope.

AY: Every night the place was open I would work the door. My routine was that I would be downtown, trying to find a way to get high. There was beer drinking, you could smoke pot.

LR: I heard that Satan’s Choice had most of the pot.

AY: No, Satan’s Choice around then was about 3 or 4 guys max, and for a while they only had one motorcycle between them. There’s a very nice house there that’s turned into a condo, they built behind it, but that was their clubhouse for about 18 months with the one motorcycle in front.

LR: So did you go to Dominion Square or something? How would you get a dimebag in those days?

AY: Well, back in [Ville] St-Laurent, where we all had friends. I never did the walk-around looking for pot. I always had a friend who had pot. Downtown was kinda weird for that, even though it was pretty open, but remember I was young then, and from [Ville] St-Laurent and this was new to me down here. I had my thing happening in [Ville] St-Laurent. It’s funny, I was doing drugs downtown, then went back to [Ville] St-Laurent and then found out, oh you were doing that [scoring] here too. Actually—just thinking about it—I probably didn’t buy a lot. There was a guy who wrote a book… Denis Vanier? He had a big afro, and if I had $5, I would go to him and ask him: “I want a nickel bag” and he would say: “How many people are smoking?” and that would be the size of the bag he would give me!

LR: That’s a ‘60s reply. It must have been an exciting gig to be able to go and work the door. Was it like today where they [ink] stamp your hand?

AY: No. We didn’t stamp people’s hand. You kept your ticket stub. Stamping the hand would have saved so much trouble. Gary had an old movie tin from the theatre. You tore the ticket in half and the other half went in there. It was an interesting time. I love music and I guess I’m stupidly honest, which has always been… ‘cause I didn’t let anybody sneak in, and I never fell for like “here, I’ll give you this if you let me in”… I just wasn’t doing that.

LR: Were you ever too honest, in the sense of saying like: “This band sucks, man”?

AY: I’ve been brutally honest at times and probably I should have kept my mouth shut, but you know, sometimes arrogance needs to be kicked in the balls! (laughs)

LR: Do you remember the shows by the Peanut Butter Conspiracy?

AY: Ah! Peanut Butter Conspiracy, one of the worst bands that ever played the Penelope! Oh my God! They were horrible! From San Francisco, we were a little nervous. They were one of those bands—and I’m there every night—and the second night, it was exactly the same, note for note… We didn’t even talk to them very much. They just came in and did that one show every night, but they were nice people, they were hippie-dips, so yeah! We took them. One of the better bands we had there was The Children of Paradise: Happy & Artie Traum, this guy Eric Katz… I got the poster and the 45 from the band… they were like a folk super-group that lasted for like 6 months.

LR: Wasn’t Happy Traum in Kaleidoscope?

LR: Wasn’t Happy Traum in Kaleidoscope?

AY: Yeah, yeah. Happy & Artie Traum, one was a nice singer and the other was an amazing guitar player.

LR: A west-coast band must have been a special visit…

AY: Very seldom. One of the traditions at the Penelope was, on the first night, which was Tuesday, we would go down to Chinatown to Sun-Sun Café and eat Chinese food with the band and the people there… we all know Chinese food… I grew up Jewish and we would do dinner #1 or dinner #2, but Sun-Sun Café, which is not there anymore, had 319 items on a a-la-carte menu. It was the first time I was ever introduced to this! And everybody would order a dish, and we would all pick off everybody else’s plate. So, a band from San Francisco, taking them to Chinatown, we were a little nervous, even Gary, who I remember saying, “Gee, I hope they like it”… well, they raved about it!

LR: So, you were there for its last weeks, the final bunch of shows? Was there any sense that [its impending closure] was coming?

AY: Not really. I remember Gary called everybody together and, I mean, people were crying, the ladies were crying, and I was pretty much shocked because I had been kind of wrapped up in that place.

LR: As the door guy, you didn’t see a drop in attendance?

AY: I wasn’t a door guy then. I got a big promotion… At first we had Mike Bunting who did the kitchen and I did the door. Mike was doing more acid than I was, for sure. Friday & Saturday are big nights, the busiest nights of the week, and he didn’t want to do it anymore. So one weekend there’s someone else in the kitchen and it’s not working out so good, everybody is a little pissed off. The next Friday or Saturday, there’s someone else working for two days and that [too] is not working out. Gary comes to me and asks: “Would I like to work the kitchen on Friday & Saturday?” and I went: “How does that work?” He says, “Well, we get someone else to do the door, you’ll work the kitchen.” I did it Friday & Saturday. My pay went up from $6 a week to $10 for the two days and then the waitresses shared their tips with me: another 15 bucks. So this is a promotion! After that, they got a bunch of people to do the door—weirdos—but it never worked out, and I never went back to the door, Gary never asked me.

LR: Do you think that they were letting in too many friends?

AY: I could see that happening. But at that point, I don’t have to pay for the show, I’m making more money than before, I could buy beer… I mean, this is good! With 40 bucks a week. I was doing great.

LR: One of the waitresses dropped a little line on the facebook group… I didn’t manage to get a reply, but she seems to remember the nitrous oxide canisters and the giggles.

AY: I don’t think we had nitrous oxide. The thing that people used to do is whipped cream canisters, but I didn’t get a buzz! I thought that that was a little weird. You didn’t drink or you didn’t smoke when you were working in the kitchen. It was pretty intense. At best, there were 200 spoons, 200 cups—I remember at one time we were down to 150 cups—and there was the washing… I’m good at organizing, so I appreciate Gary for taking that little nerd at the door—who’s just doing nothing…

LR: Tell me about New York City.

AY: I got to see Cream in New York. Going to New York was like Mecca. One time I went down with my friend Ed, got drunk one night and ended up going down there. We were there at Café Wha? And we’re going “Jimi Hendrix!! Ah shit—last night—fuck!” Right next door to the Café Wha? Was the Café a Gogo and it’s the Cream—tonight! That was the first tour and there was nobody there! I’m sitting there leaning back with my feet on the stage… with Eric Clapton in front of me! It’s a small place, there can’t be more than 25-30 people. It’s not even like a third full. The story is, they’re doing their set and it’s great. They’re doing their first album—it wasn’t released in the States, it was released here and everybody is going crazy for it!—and they go into “Toad” and they go off stage, leaving Ginger Baker there doing a solo, and this goes on forever.

And he falls off the stool and is lying there. So they hear [that] it’s quiet, they look back out and see him laying there, and they’re sitting there talking to him, putting a cigarette to his lips… and we’re sitting there watching this. He is white & red: white face and red around the eyes and he’s over-amped for sure! That was like 10 minutes, but they pick him up, put him on the drumkit and finish the song, and that’s the end of the first set. After a long break they actually play a second set. I actually have the menu from that night.

Back to Montreal—they’re playing at the Paul Sauvé Arena, and they’re booked to be the opening act. On the way out to [the place], they come by The Penelope and I’m at the door and someone says: “The Cream are out there!” I go outside and there The Cream in a limousine, the windows down and I’m looking at them and I can tell that they’re not playing tonight… they are fucking WASTED! What we didn’t understand was that the speed in Montreal was better than anything they had ever tasted, and they were FUCKED UP!! They couldn’t play. It was pretty much sold-out because The Cream are big here, but The Rabble had to do the whole show. They were told that they can’t play and you’re it! I wasn’t there because I was working that night. I heard later that The Rabble were a little nervous, but they played every song they knew and they gave it everything.

LR: Why was the limo at the New Penelope?

AY: I have no idea.

AY: I have no idea.

LR: This was a few months after you saw them in New York?

AY: Oh yeah! They were on tour, it was a long and disastrous tour because through the States, nobody knew them, and they were so fucked up!

LR: Speaking of The Rabble, did you see them live there or elsewhere?

AY: I saw The Rabble lots of times. Pimm has got a great voice.

LR: You didn’t only go to The New Penelope, right?

AY: Well, at that time, I didn’t like The Forum for shows, so I didn’t go to many… [the sound was] terrible, terrible! I forced myself to go see Led Zeppelin twice and you could tell when they changed keys because the place vibrated differently… I saw Zappa in the early ‘70s, there again, the sound was terrible. One of the things about The Penelope, the sound wasn’t that bad.

LR: Supposedly, Zappa was the first act to play two weeks or whatever when they moved to Sherbrooke Street.

AY: Yeah! He was the first act.

LR: Supposedly, he had them re-arrange the speakers and stuff right off the bat.

AY: I don’t know but… I always remember that there was two in front, two on the side, and later on going: “Oh! That’s how they do it!”

LR: What about other venues?

AY: There was the Black Bottom. I didn’t hang out there, but I went there a lot. Coltrane played there. I saw local musicians there, many, many times, I saw Raahsan Roland Kirk there. They used to have a restaurant in there and they made great food, great southern cooking. That was in Old Montreal, one block in from St-Laurent on St-Paul. Back then, it was actually empty. You would go down there and do acid trips because nobody would bother you. Nobody was there at night. There were some clubs, David the candle-maker was down there, remember sand candles? They had molds and poured in the wax and pulled it out and you’d have sand on it, with the legs… he made them down there in his hippie shop. There was the Boite A Chanson too. There was lots of stuff happening, but you had to root it out.

The McGill Ballroom had some things, I remember the first time I ever saw ‘Walking’—Ryan Larkin’s movie—was on acid in the Ballroom, and it’s something to see on acid! You don’t know if you’re hallucinating or not!! (laughs)

LR: People used to tell us about going out at night and missing the last bus to get back home, and there was this place called The Bus Stop…

AY: The Bus Stop was near Sherbrooke at Guy. There’s that sort of fancy building and when you go behind it, the old houses that are set back, it was in the first greystone in the basement. I spent time there and at the delis, the all-night delis: Ben’s was one, but my favorite was Dunn’s 24-hours, but you needed money. The Bus Stop was when you had no money, because you could just sit there. If you had money, you had yourself a piece of cheesecake and a coffee!

LR: What else about the sad ending of The New Penelope. You must have been sad too?

LR: What else about the sad ending of The New Penelope. You must have been sad too?

AY: Yeah! Basically I was in shock! It didn’t really dawn on me until a couple of days later… what was going on. I pretty much knew that I was going to do—go out and find another job! See, jobs were easy back then, it was a whole different thing to go out and get one, at a buck and a half an hour. You would just go out and get work.

I ended up working in the Cote Vertu shopping center, near l’Acadie, which was slightly more built up then, just past the train station. There was a Broasty Chicken, an American company that came up here, I got a job there. Two women owned the place, and every night we drank 48 beers and at least a 40 ouncer of Rye, at least! I stayed there at least a year—I quit or got fired—whatever it was, I ran away! (laughs) It was too crazy! The chicken was great, it was unbelievable fried chicken, they cooked it in pressure, so the chicken came out not greasy. That was in 1970.

LR: But what about the loss of this place where you had your fix of live music every night? What took up its place?

AY: There wasn’t really a lot happening back then. Place des Nations that had great shows for many years after [Expo 67]. The sound was iffy, it was outdoors, and really depended on which way the wind blew, I’m not joking! Records were important.

LR: Where did you buy them for the most part?

AY: Records were $3.98. The Record Centre, that helped a lot of people.

LR: What about daily life? When you got your first place, what was the rent?

AY: My first place, I rented with a friend of mine, I don’t even remember what we paid but it was low. Then I rented a place with Gayle across from where Tepley had his store—that was a 6 1/2—$88 heated and it had a fireplace! It was above Betty Brites [dry cleaners] right on the corner of MacDonald & Decarie. I remember Gail’s reaction when I showed her, she went: “It’s too big!” so I closed 2 doors and said: “It’s a 4 ½ and it’s still $88 a month!” It was right across the street from The Texas Tavern, and next to that was the Galaxy Hotel & Bar. In high school, I remember the bartender at The Texas going: “Eh! Stop coming in here with your school bag!” and I’d go: “Oh! Sorry, sorry!”

LR: So, you commuted from St-Laurent to McGill when you started working there?

AY: Yeah, I took the 17 bus, or would hitchhike, then we got bicycles—anything not to take the bus. The bus was so dreary! I remember the snowstorm of ’72. We started to go to work and Decarie was blocked—we’re troopers!—we walked over to Saint-Croix, get the 16, go through TMR and we ended up walking back home—we got stuck in TMR—that was a good one! There was so much snow that these guys got snowmobiles and went around robbing the banks! (laughs) The cops couldn’t catch them!

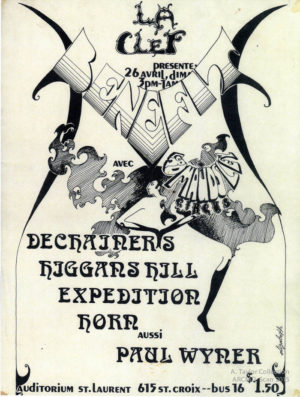

A poster for a 1970 benefit show for promoter Alain Simard (later founder of Montreal’s Jazz Festival) in Ville St-Laurent, from the collection of Alex Taylor.

Back then the Texas was old-school, opened at 8 o’clock and there were people there at ten to 8! It was that type of place, but the other clientele were of a different ilk, they were gangs, trouble. The first ethnic community in St-Laurent was what I called Little Israel. There was Alexis-Nihon around it, and it was a completely Jewish neighbourhood, almost everybody that was there was Jewish. When I went to Winston Churchill High School on a Jewish holiday, it was empty!

There was the old part of St-Laurent which was very Catholic and French Canadian, then there was the Anglophone area which was probably up around Decarie & the Crevier apartments, and then there was the Jewish district, I delivered papers to that whole neighbourhood.

LR: You lost some friends, I guess, to Toronto by the time ‘ 75-’76 approaches? The PQ comes in and there’s this business of the exodus…

AY: Yeah. We were pretty much politically naïve back then because that whole thing pretty much happened without us. I figured it out after it happened—the whole French-English thing. There was tension because during the riots there, they were using razor blades on the [police] horses. It was nasty, but that was happening during the Penelope time. Leading up to that time after high school in St-Laurent, it was pretty much out of the picture for me. There was no sense of that at all. See, the Quiet Revolution was called that because it was exactly that—it was quiet!

LR: But you weren’t in a 100% anglo environment at Winston Churchill?

AY: Oh, the school itself was 100%. Mike Fauquet my best friend was French-Canadian, but he spoke French and spoke English. He was basically an artist, so he didn’t give a shit about that, and Roger Rodier, he was over at the house many times, and if he spoke to you, he spoke English perfectly, and French perfectly and he wrote only in English, it was that type of thing. His album was amazing at the time [1972], but I think he got really disillusioned by the reaction in Quebec and of course, anybody in the record business is going to get fucked over. I hung around with Mike and Bob Panetta—he’s not Italian—he’s French! Strangely, the thing was, they all spoke English & French, and I only spoke English.

LR: Do you remember where you were during the October Crisis?

AY: I was at McGill. We were going down and there’s the army everywhere! I’m too old, so my reaction to it has been filtered through so many years, so I’m trying to capture my reaction back then. It’s difficult, but yeah, definitely don’t like guns and army guys on the street, but that was an interesting time. I never voted Liberal but I kinda liked Trudeau. The thing he did with the Kellogg’s Corn Flake boxes—the bilingualism—I mean, if he would have made the country bilingual, there would have been a riot, but all he did is he said: “If you’re gonna sell Corn Flakes, in Calgary you could turn it around to this side and in Quebec you can turn it to the French side.”

And then I think it took 30 or 35 years, until some guy in Manitoba went: “If I can get my Corn Flakes box bilingual, why can’t I get my parking ticket in French. And the Supreme Court said: “The guy’s got a point!” Trudeau, that’s the type of far-thinking guy he was. You can force Medicare down their throat, force Unemployment Insurance, but you can’t force language. But back then, I was ambivalent about all that. Didn’t know what to think but, I didn’t like it.

LR: So when Rene Levesque wins the election in 1976. No big reaction?

AY: I never voted PQ, no. I was never that naïve. I was naïve in the beginning—in the ‘60s when the independence movement came out—there was something about small democracy and the left that appealed to me, so I tried to participate, but being Anglophone—I bumped into, guess what?—bad vibes (laughs) I contacted the Parti Québecois and they wouldn’t talk English to me! So I’m going, “I’m interested in what your talking about but – because I’m English – you won’t talk to me, I get it!” Trudeau wrote something around the same time, he said: “You scratch a separatist and you’ll find a conservative!”

What’s basically happened, from my perspective, is that the Catholic Church used to be the protector of the French language. Then the Quiet Revolution broke the control of education from the church and gave it over to a secular system. But if you wanted to go into business, well, you still had to go to an English university, so up to that point, if you wanted a degree, you spoke English. So basically, nobody saw it coming, because they’d been hiring Francophones who fit in so well—Gee, what a great education system!—so it became more difficult when you had the first graduates in ’64 and’65 speaking French only. That’s when the Quiet Revolution got noisy…

LR: Did you feel forced to think about moving in ’76 when—no doubt—you had friends that left?

AY: Oh, everybody at that point. My sister worked for BP and they moved their head office, and my God, she made a fortune! They helped her move, helped her buy a new place. I mean, why not go?

But all of that stuff needed to happen. The easiest thing to look at is Vermont: Vert Mont, the green mountains. All the French names, they’re all anglicized! If you take a look at that… something has to happen. If we’re gonna be all English, we’re gonna fall to the Americans eventually.

LR: Well, I’m glad you stayed.

AY: Well, McGill never moved! And it has been very, very good to me! I never finished high school. I didn’t like school. The irony is that school has been my whole life! I get to go to school everyday for my working life. They’re gonna give me a 45 year pin for working at McGill, but I’m not gonna go to the ceremony!

Allan can still be seen at concerts around town on a regular basis.

I later got to know him at Barfly and was beyond appreciative that he approved of my work.

This article gives a great amount of depth to both him and the music-scene history of Montreal. What a great read, what a great man, and what a great city! Thanks!

..the penelope was school for all of us..sidetrack, butterfield, muddy...earth opera(google that one), tim buckley...mothers ...the list goes on and on.. goes on and on....

..and little did i know that if you reversed '67 to '76...i would be playing with the skinny kid from memphis...

He brought in some great folk performers: Dave Van Ronk, Rev. Gary Davis, John Hammond Jr. and more. I recorded some of the shows and have digitized some of them. I wonder if there is any interest in hearing those performers...

e mail me and i will return the picture.

In 1971, I shared an apartment on Souvenir St. with several members of the Sidetrack including John Lewis and his wife Sandy. Then one day, John contracted a terminal cancer and quickly headed back home to the States. Very sad.

John was a great guy, and a marvelous story teller. His first cousin was John Sebastian of the Lovin' Spoonful and those two shared a grandfather, also John Sebastian, who was a world-famous harmonica player.

I have no picture of John or indeed any pictures from the New Penelope or Sidetrack and would greatly appreciate receiving a copy of any pics you would care to share.

Cheers,

After work Gary and I and some of the people would go up to Mount Royal and smoke a joint and wait for the sun to come up. My name is Helga.

I came from TMR, as were half of the guys in Sidetrack. I was playing Keyboard in another band from the Town with Andy Higgs, who became Sidetrack's bass player. Sidetrack was the New Penelope's house band in 1967, but somehow our Band, Owed to the Blues, was able to wangle a gig as the "backup" house band on Sunday Nights. Sunday was usually pretty dead and if we were paid anything it was a pittance. The BIG payoff was that we were able get in free for many shows and hang out there as if it were our clubhouse.

I had access to my parents Chevy so I also occasionally helped Gary out by picking up musicians to bring to the club (Sonny Terry & Brownie McGee) or in one case (Darius Brubeck) up to the NFB for a filming session.

I also have great memories of the Swiss Hut which had the most amazing mix of people - a true Montreal mish-mash of franco separatists, artists, hippies, Sir George and McGill students (often patrons of Gary's place), plus working types who usually viewed the long hairs with a mixture of mistrust and contempt. My own not-so-long hair and apple-cheeked innocence gave me a fairly benign appearance which helped me to strike up some interesting conversations at the bar with "straights" from different walks of life. In particular I developed a friendship with two older guys who worked in maintenance at Morgan's department store (which had been rechristened as the Hudson's Bay a few years prior).

It was surprising how boldly one could smoke weed in the Hut. Of course, in those days the air was already blue with cigarette smoke. One evening, a group of us were in a booth waiting for our dinner and merrily passing around a fully loaded chillum. Then the cry went up that there was a police RAID in process. I was literally in mid-toke at that moment so I had to discreetly dispel a huge lungful of smoke and launch the pipe along the floor. I think the target of the raid turned out to be some specific people, not a general drug bust, so in the end we were able to finish off our meal and head back to the New Penelope.

The New Penelope and the Swiss Hut, Le Drug, Chez LouLou (aka The Bistro), The Esquire, The Blue Angel ... so many great places have come and gone.

At least we have the memories!

Get in touch, I'll let you know why Im asking. Cheers

I worked at he Boys Home of Montreal 1968/9, and frequented a number of places where music was on offer. I recall a pub on Mountain Street - The Seven Steps? - where, in return for acting as doorman I got free beer! I also went to the New Penelope Nightclub to see the Paul Butterfield Blues Band just after Mike Bloomfield had left and was replaced by Buzzy Feiten. Also bumped into Leonard Cohen and Pete Seeger. Great times!!! Weymouth, Dorset, UK