Ken Norris, Véhicule Poet

Ken Norris was one of the “Véhicule Poets”, an informal bunch of poets who hosted and participated in readings at the Véhicule Art gallery and performance space on Ste. Catherine St. in the early to mid 1970s. He has more than two dozen publications of poetry to his credit and has had work appear in countless anthologies. Born in New York, he now teaches creative writing and Canlit at the University of Maine. Louis Rastelli corresponded with him for the following interview about the Véhicule Poets era in Montreal.

LR: When did you first come into contact with what we can call the small press,

self-publishing milieu in Montreal?

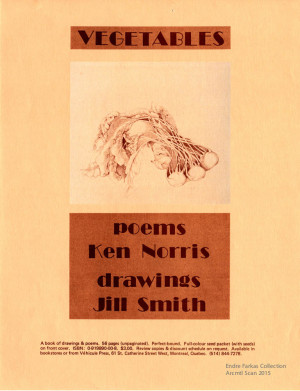

KN: Everyone finds their own unique entrance into this realm. My path was kind of carved out for me by a visual artist named Jill Smith. She and I had been working on this collaborative project together. She was doing drawings of vegetables, and then I was writing poems in response to her drawings. Folks who have seen the book that resulted, Vegetables, which was my first book, probably figure that I wrote the poems and then Jill did the drawings, but in point of fact the drawings came first.

She did the drawings and then I wrote the poems. Anyway, we’d been working on this project for maybe a couple of years when she decided to take it down to Vehicule Press, which was in its early days, sometime towards the end of 1974.

And they liked the project and decided that they would like to publish it in book form. I got a phone call from Jill telling me that our book had a publisher when I didn’t even know we had a book or that we were looking for a publisher. So having my first book in the works at Vehicule Press was what brought me into the orbit of the Montreal small press scene.

I must have popped in at the press in early 1975, and couldn’t help but notice that they were located in the back of an art gallery called Vehicule Art. And someone, Simon Dardick probably, mentioned to me that there were poetry readings at the gallery every Sunday at 2 p.m. So I started showing up for readings in January, and by March the book was in press, and by the end of March it was in stores like Classics, The Double Hook and The Word. By the middle of April it had been reviewed in The Montreal Gazette and I was doing interviews on the CBC.

At the gallery I met printers, and artists, and poets. By the end of 1975 I was on the editorial board of Vehicule Press,; by the end of 1977 I was a member of the Board of Directors of Vehicule Art; and by early 1979 I was in an anthology of seven poet s called The Vehicule Poets. With a friend of mine in New York, Jim Mele, I was also running a little magazine, CrossCountry, and a small press, CrossCountry Press.

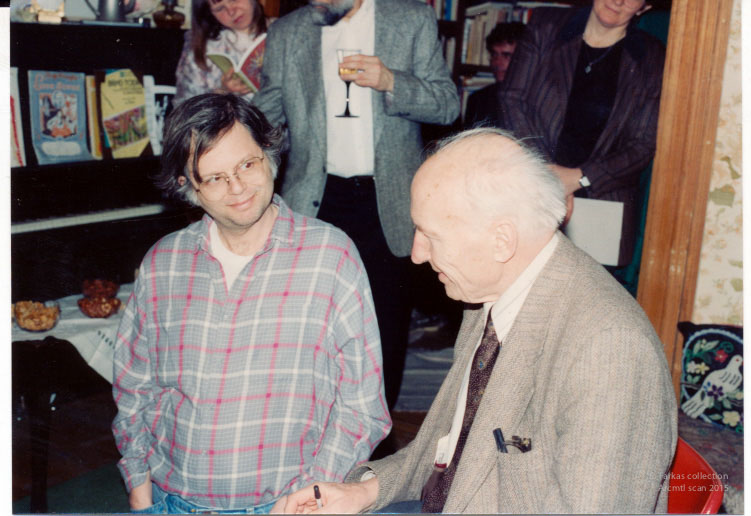

In September 1975 I started working on a Ph.D. at McGill, and the professor I was most interested in working with was Louis Dudek. For the next five years I quizzed him about all of the small press activity he had every been involved in (Contact Press, Delta, McGill Poetry Series, CIV/n, DC Books) and tried to apply some of that forties and fifties small press methodology to what we were doing in then contemporary Montreal.

LR: That is interesting. I would have loved to have the opportunity to work with Mr. Dudek, a living legend at the time!

KN: He was a living legend, but he was also a Professor at McGill. The first time I went to see him were during his office hours. I introduced myself to him as a student newly arrived in the Ph.D. program at McGill and gave him a copy of my first book, Vegetables. I had spent part of that summer reading his long poem Atlantis, and also looking into that book that he had edited with Michael Gnarowski, The Making of Modern Poetry in Canada.. I was learning a lot about Canadian literature on a daily basis, and when the Graduate Director of the English Department asked me what course I might be interested in being assigned to as a teaching assistant I said “Canadian Literature.” Even though I didn’t know very much about Can Lit at that time. I figured that teaching it would be a very quick way of learning about it. But I was already starting to pursue my study of Canadian literature with what could be described as a missionary zeal. And who better to learn from than Louis Dudek? But he wasn’t teaching the Introduction to Canadian Literature course—Marianne Stenbaek was.

So I audited one of Dudek’s graduate courses in Modernism, giving myself a reason to show up in his office on a regular basis to ask him quiz questions about everything from Contact Press to who Irving Layton’s favourite poet was back in the 1940s. Answer: D.H. Lawrence.

LR: I know you were originally from New York and moved here in the early 1970s. What motivated your decision to live here?

KN: I was accepted into the M.A. program in English at Sir George Williams University and was offered a tuition waiver and a research assistantship. By the time I graduated Sir George had merged with Loyola to become Concordia University. I didn’t study ANY Canadian literature as an M.A. student. I was still very committed to American literature and wrote my Master’s thesis on F. Scott Fitzgerald. I started getting interested in Canadian literature a couple of years later when I found myself on the road to becoming a Canadian author, or an author who was being published in Canada.

But, you see, by 1975, the Modernist period in American literature was over, and all of the Modernist authors had passed over to the other side. In Canada, because Modernism had started in Canada maybe 15 years later than it had in England and America, many of the Modernist writers were still alive. F.R. Scott was still alive, and I went over to his house for tea. A.J.M. Smith was still alive, and I went to hear him do a poetry reading at the Cote St. Luc Library. I corresponded with Earle Birney and edited a selection of his essays for Vehicule Press. I met Dorothy Livesay and she invited me to be the Quebec representative of CVII. In later years, Simon Dardick, Peter Van Toorn and I tried, unsuccessfully, to get Leo Kennedy to do his second book of poetry.

To be able to have actual conversations with the Modernist poets of Canada was something that really wowed me. It moved me more in the direction of being a Canadian poet. Because an American poet couldn’t talk to Ezra Pound or H.D. or William Carlos Williams or T.S. Eliot—they were all deceased. The Canadian Modernists were still among us. And I could also talk to Louis Dudek, and have dinner with Irving Layton, and send Raymond Souster the occasional fan letter or a request for poems for my little magazine. My feeling about Canadian literature was that it was ALL HAPPENING NOW. Whereas American literature had had its Golden Age and had moved along to something else.

LR: Aside from the Vehicule artist-run centre and the universities, were there any cafes or venues where you and/or other writers would hang out, draw inspiration, people-watch or take in readings?

KN: The first time I ever did a poetry reading it was at The Double Hook bookstore in Westmount in the Spring of 1975. I shared a reading with Claudia Lapp. And I think the first solo reading I ever did, later in that year, was at The Word bookstore. So bookstores were a really important part of the equation. Artie Gold and I used to hang around The Word “frequently.” Artie was in there just about every day, because he lived just up the street, and I was in there pretty much every day I was in at McGill. After my teaching day was done at McGill I would hustle over to The Word, to see what new books were out, or what was new in the poetry section.

LR: Do you recall the first time you walked over to the Vehicule space—that area was still the red light district, was it not?

There were streetwalkers on Ste. Catherine Street, and there were more of them in the evening. Red light district is a little too gaudy—it was a rundown neighborhood, which is why the gallery was there—cheap rent. I don’t think that made much of an impression on me. I was more intrigued by the fried egg sandwiches and pecan rolls at the Eldorado!

I don’t remember the first time I went to the gallery, but I figure I went over there the first time to visit Vehicule Press, which was located in the back room of the gallery. And it was nothing much to look at. There were a couple of printing presses, one big one and one smaller one, a couple of printers, a couple of other people working there. I don’t know if the printing cooperative ever exceeded five or six people. I was probably there to introduce myself to Simon, since he was going to be my publisher.

LR: For all the references to this space that people we’ve spoken to have made, no one has yet described the experience.

KN: White walls, wooden floors. A large gallery space. The “office space” was up on a second level. The Press was in the back. There was an old out of tune piano. On weekends the heat was turned off, so if you went to a Sunday poetry reading in winter you kept your coat on, and if you were doing the reading you kept your coat on. “Vehicule Art” was in neon down at street level, and you had to climb a formidable flight of stairs to get up to the gallery. There were rickety wooden chairsto sit on for readings, so often I sat on the floor.

I have to say I fell in love with the gallery at first sight. I just loved the space. Maybe the musician in me was feeling all of the old-time jazz vibes. It had a good feeling to it. The place exuded possibility.

LR: As a decaying former nightclub, I would presume that Vehicule must’ve felt like a place of transition, taking up an entirely new practice of culture in an area that saw the best of nightlife and cabaret culture from the 1920s-1950s.

KN: The past had been erased. It was years later that Simon told me about the Montmartre. The first generation of artists had done a fabulous job of renovating the space and making it feel NEW. And the artwork was all alternative, experimental, sometimes excessively weird, just crazy conceptual stuff. The parallel galleries were set up as an ALTERNATIVE to conventional commercial gallery spaces, and Vehicule definitely took advantage of its alternativity. We all walked in as one kind of poet and walked out as another kind of poet because of our exposure to the art, the environment of the conceptual, the permission and the demand to be absolutely up to date. There’s a certain tendency towards traditionalism in poetry that the gallery just drove out of the Vehicule Poets. I was pretty conservative in my artistic tendencies before I arrived at Vehicule. And all that stuff got jettisoned right quick. Part of it was because of the poets I was talking to, like Artie Gold and Tom Konyves, but a lot of it was because of the environment I was in. In 1975, I was probably in at the gallery for some reason or other six out of seven days in the week. I was hardly ever there on Saturdays. So I was coming into contact with the experimental contents of the gallery on an almost daily basis. That started doing funny things to the inside of my head.

LR: You mention running the small magazine CrossCountry—for the sake of understanding how one went about such an activity with no recourse to word processors, photoshop, layout software or laser printers, how the heck did you manage this? What were the steps in the mid-70s in setting up and then producing issues of a new periodical?

KN: Believe it or not, there was life before personal computers. CrossCountry magazine ran for sixteen issues (1975-83) and CrossCountry Press produced twenty-three books in roughly the same time period. We started it all with a grubstake of $300. In the old days you hired typesetters to typeset and printers to print. That being said, I did a lot of typesetting when given access to the equipment. But printers in New York, Montreal, Toronto and Michigan printed our magazines and books, depending upon who came in with the lowest bid.

It started the way it always starts, with a couple of people saying “Let’s start our own little magazine!” And it takes off from there.

LR: I would assume some of the steps would include: coming up with a name, a policy for submissions, sending out (by mail? by word of mouth?) a call for submissions, deciding on a price and how it would be sold (distributors? consignment in a few local shops? Subscriptions?) whether it would break even (assuming that no writers were being paid, and that break even means just paying off the printing and postage costs).

KN: All true. Let’s tackle them. Jim Mele was in New York and I was in Montreal. As we talked about it we decided that what we wanted to have was a magazine that focused on both Canadian and American poetry. We didn’t realize we were walking into something of a minefield, but more on that later. So we had to come up with a name, so we called it CrossCountry, no space between the words. I can’t tell you how much junk mail we received in a ten year period related to cross-country skiing!

Up until 1990 writers lived their lives via post. Everything happened in the mail. You sent your manuscripts to magazines or publishers through the mail. You got your acceptances or rejections through the mail. You sent other writers letters. Literary correspondence was a big part of my life. Magazines and books arrived through the mail. And on and on and on.

Having come up with a name for our magazine, the first thing we did was try and recruit institutional subscriptions. Through the mail. I don’t remember how many libraries and universities we attempted to contact. I think we got around one hundred replies constituting one hundred subscriptions. It was a place to start.

We contacted writers we liked—through the mail—and asked them to send us work. Many of them did. We were off and running. Early issues were hand distributed to independent bookstores in New York and Montreal. By something like the fifth issue we had small press distribution in both Canada and the U.S.

You could kind of break even, or come up with enough money to print the next issue. But then the granting organizations came into the picture: the Canada Council and the National Endowment for the Arts. For a while they liked what we were doing, so we received funding. When they got tired of us, and all the money was spent, we folded the magazine and the press. But we did close to forty publications in eight years—that’s not bad.

LR: Did an editorial team or just yourself and your co-editor then read and select

the works?

KN: In the early days Jim and I selected the poems for the magazines and the books for the press together. After a while, as we grew more confident, we started making individual decisions. There were entire issues that I edited in Montreal and entire issues that he edited in New York. Where the issue of the magazine was produced, which country, depended on which arts agency was funding the issue, and which printer in that country was offering us the best price. When an issue came out we sent out two copies to every contributor—through the mail!

LR: I am particularly interested in learning a bit about how it ended up being printed on Vehicule’s presses. They were co-op—did this mean you had to pay a fee regularly to use it, or pay the pressman when you needed to use it?… Did you supply paper? How did it get printed then collated then bound? Did volunteers gather to help with typesetting, collating, etc.?

KN: I was on the editorial board of Vehicule Press by around September or October of 1975. But when it came to bringing CrossCountry magazine, for instance, in to the Vehicule print shop I was just another customer. So my view of the print shop, as a publisher and editor of CrossCountry, was and is as a customer. Their business model may have been that they organized themselves as a cooperative, but as a customer they were just another printer. They needed to make enough money to pay salaries and pay their bills so they needed to make a profit on every print job that they did. So, as an editor and publisher of CrossCountry, I hired them to do a job as I would hire any other printer. And one expected the same degree of professionalism that one would expect from any other printer. So collating and binding was their job. They delivered a finished product for a specified price and I paid the bill.

When I had my Vehicule editor hat on it was completely different. Because I was, in that instance, an unpaid employee of Vehicule Press. I selected and edited manuscripts for them, and they undertook the financial risks, rewards, and responsibilities of being the publisher. Having their own printing presses helped them to keep the costs down.

My best guess would be that, of the sixteen issues of CrossCountry, maybe five or six of them were printed at Vehicule. The first couple were printed in New York, the last one at Coach House in Toronto, a few in the middle in Michigan.

LR: You mention the Eldorado—was this what has been described as a sort of cafeteria with vending machines? Did you ever go down to the hot dog joints around the corner (Coin Dore, Frites Doree, Poolroom) or to the Woolworth’s across the street for lunch? Were there old taverns—old man bars in the area that artists and poets frequent for cheap pints after events or readings?

KN: I am not going to say that there were no vending machines at the Eldorado, but if there were I honestly don’t remember them. I had my “Eldorado diet”—and that was a fried bacon and egg sandwich on white toast and a pecan roll. I got that direct from the counter. They fried up the eggs and bacon before my eyes and then they cut the pecan roll in half and buttered it. And I would imagine that I rounded that out with a small carton of milk, but now I’m guessing. Maybe it was tea.

I never ate at Woolworth’s. Ever. When Artie Gold was down at the press or the Gallery during the week—which was rarely—we definitely were around the corner with the hot dogs and the frites.

At least a couple of times we went into a tavern around the corner on St. Laurent. We had a few informal meetings there and one time we wrote a collaborative poem there. I think the poem is included as a footnote in Tom Konyves’ book Poetry in Performance.

LR: I’m not sure if you’re aware that pretty much that whole block/area is slated to be demolished for high-rise condos. Would you feel any regrets to learn of the complete demolition of the four storied corners around which Vehicule Art stood, or would it just be another change in era, such as how you mentioned the glitzy nightclub era had long faded by the time you guys took up shop on that block…

KN: Nobody likes hearing about the demolition of the sacred sites of their youth. It’s horrible, terrible, sad. But you get a lot of that by the time you’re in your sixties. Half the places I lived in Montreal have been torn down. Artie’s gone out into the universe. The place where I used to live when I lived just down the street from him has been torn down. I don’t know if the place where he lived in the McGill ghetto is still there or not. The next time I’m in town I will have to look. But I’m still in the gallery, and the gallery is still in me.

LR: Some have argued that the corner of St. Laurent-Ste. Catherine is somewhat at the heart of Montreal’s literary imagination, being close to the border between Old Montreal and modern downtown, and between the English and French halves of the city. . However, I’m not sure I’ve seen much reference to the area of “The Main” in general in the works of Vehicule poets. Was this perhaps a subconscious reaction against sounding like the Mordecai Richler generation of writers who so mythologized the Main?

KN: Let’s start with this: I have a long poem called Boulevard Saint Laurent which is included in Report 16-22. It’s a love poem to the Main. It starts down at Notre Dame Cathedral, travels all the way up to Jarry Park, and then heads back downtown, ending on the corner of Boulevard Saint Laurent and Milton Street.

So I went out of my way to acknowledge the importance of that street in my life and in the lives of many Montrealers.

If Tom Konyves had ever been able to find a parking space down around the gallery (St. Laurent and Ste. Catherine Street) I doubt he would have ever written his wonderful poem No Parking.

Those are the two “documents” that come most readily to mind. But the poetry of the Vehicule Poets is SATURATED with Montreal references that range out over the entire city, extending out onto the West Island. I agree that The Main is important. But then so are all of the other streets.