Early Days of the Montreal Small Press

At our annual Expozine small press fair, specifically on November 16, 2014 a round-table discussion on the early days of the contemporary Montreal small press scene was held.

The panel consisted of the founding members of Véhicule Press, Simon Dardick and Nancy Marrelli, and the founder of Montreal’s long-running independent bookstore The Word, Adrian King-Edwards.

Véhicule Press began in 1973 on the premises of Véhicule Art Inc.—one of Canada’s first artist-run galleries located in what was once the legendary Café Montmartre night club. In 1975 the press became Québec’s only cooperatively-owned printing and publishing company. Simon Dardick and Guy Lavoie were general editors. In the seventies the press distributed most of the small English-language literary presses emerging from the city. Simon Dardick and Nancy Marrelli continued Véhicule Press when the co-operative was dissolved in 1981, and they are now publishing more titles than ever.

The Word Bookstore was opened in 1975 by Adrian King-Edwards, who was already by then an important collector of Montreal small press and self-published publications. It is the oldest running bookstore accepting local publications on consignment in Montreal, having sold hundreds of different titles by hundreds of local authors in its long history. Adrian King-Edwards is also one of the organizers of Montreal’s annual antiquarian book fair.

The following is an edited transcript of the discussion, moderated by Louis Rastelli, co-founder of Expozine and publisher of the noted underground Montreal magazine Fish Piss.

Simon Dardick, Véhicule Press (SD)

Nancy Marrelli, Véhicule Press (SD)

Adrian King-Edwards, The Word Bookstore (AKE)

Louis Rastelli, Moderator (LR)

LR: When did you first come into contact with what we can call the small press, self-publishing milieu in Montreal?

SD: I have to say that I’m a refugee from Kingston, Ontario. I came here in the 60s but before I came here, I used to read all the literary magazines and books published that emanated originally from Montreal. I used to read books by Louis Dudek, Ray Souster, books that were created by them under the name Contact Editions. So before I came here I was already prepped and felt that Toronto didn’t have an appeal to me; I’m not Toronto-bashing, it just didn’t have the same literary appeal that Montreal had. So before I got here I was interested in literary things from here. But then when I came here, I guess you hang out, you know? We used to hang out at the Swiss Hut on Sherbrooke Street, not far from the New Penelope, which was a club nearby. The Swiss Hut had a real amazing mix of people, you had political people, you had Felquistes, Union organizers, a literary crowd, just an amazing crazy place. I started to get a feel for a certain scene at that time.

AKE: I also came from Ontario and went to McGill, I started at McGill in ’67 and studied English Literature. And like most English literature students, I wanted to be a poet, a writer. I took creative writing classes, after I graduated I went travelling through Europe. I came back at the age of 21 or 22, and felt it was time to write my memoirs (laughs). I found a little closet on Lorne, in the basement, which had a hotplate in the hallway, and a mattress on the floor, a desk and a typewriter, and I figured I was all set ready to go. The closet was costing me $8 a week so the overhead was really low. I had wisely given up on the poetry – I was concentrating on my memoirs.

Then I got sidetracked, I met my wife and we went off to British Colombia and we spent the summer selling books out of our Volkswagen van. You couldn’t do it in municipal areas but you could do it in places like trailer camps, mining camps, lumber camps and the like. So we travelled through BC selling books. So this was still literary ambition but it was shifted a little.

I came back to Montreal and wanted to start a bookstore, I figured that would be a really fun thing to do, and I found an apartment on Milton Street, immediately next to where the store is now for $100 a month, it was a 4 and a half. I haven’t checked lately but I think it’s gone up quite a bit. All the doors along Milton Street were the same and we both had been in the English department and we wanted to appeal to students at McGill to come and buy second hand books so we put a picture in the door of George Bernard Shaw, which indicated that that was the door where the cool underground bookstore was.

People started coming, it was very popular we really enjoyed it. We really wanted to connect with the poetry community and this was ’72 ’73 that was exactly when things were starting. We just coincided exactly at the right moment.

One day Fraser Sutherland, who was the editor of Northern Journey, came by, he’d been sent by Mr. George at Argo – Mr. George is certainly one of my mentors – and he wanted to know if we would carry Northern Journey. At that point I figured we had totally made it, we connected with the literary scene.

We went on from there and had poetry readings in our apartment above once every two weeks. To the point where there were so many people coming and going that one afternoon two policemen showed up and we got raided. They went through all the spices in the kitchen. One of them got bored and ended up lying on the floor in our closet playing with some kittens that had just been born.

Anyway, they let us off and went on their way but we did this for about a year and a half and we met, at that time the literary community was really small so you could have a sense of virtually knowing everybody in the English language community.

It was really an exciting time to be around and everybody was starting out: Fred Louder, Villeneuve Press, starting out doing fine printing, the Véhicule Readings were starting, the 70’s were really solidly Véhicule Readings, Sunday Afternoons, we would go to readings there at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, I have a poster in fact, I’ll show you after of the Véhicule Readings from 1975 to give an idea of how active they were.

So at that point we were looking around for storefronts and being torn about whether we should really look for a storefront or just find one. One day I came out to walk the dog and the building where (The Word Bookstore) we are, was a Chinese laundry and the sign said: for rent.

That was just a no brainer, this has to be the thing to do. So we went in there and things were a lot easier in ‘75, the rent was $175 a month and we were selling books outside for 25 cents, books shelved alphabetically on the shelf in alphabetical order were 35 or 40 cents… it was easier times.

We continued the poetry readings and we also did some publishing. We published, along with Fred Louder, some fine press editions and Brian McCarthy was also a poet then. He lived on Saint-Laurent just above where the grey stones are, the monuments, and he was moving to Europe and I managed to buy his poetry collection, which was a spectacular achievement for somebody starting out. I managed to get his Gestetner machine because a lot of things in the 70’s were produced on Gestetner. So we started Gesterner-ing author stuff. This one (holds up a stapled set of sheets) is a short story by a friend of mine, Wayne Grady. This we sold for 35 cents.

LR: Just to clarify — a Gestetner is a hand-cranked cylinder press and you would type out pages on a typewriter and just make copies from it.

AKE: Yes, and we did some fun broadsides like this. This one is Guy Berchard, who now lives in Victoria; Laurence Hutchman, really nice, one of my favourite poems, The Chinese Man. I’ll show them all to you after if you are interested—here are things Fred Louder did. One of my greatest disappointments was that Fred Louder who did such magnificent work on his press moved away and I had foreseen working with him for quite a long time. And here: five jockey poems by Artie Gold.

LR: The Powerhouse which eventually became La Centrale Powerhouse has taken part of Expozine a number of times actually along with Véhicule, it’s weird that there is such a connection back then to now.

NM: Véhicule started out as a gallery, as the first artist-run gallery in Montreal and the second artist-run gallery in Canada. Powerhouse was the women’s run gallery which was very, very important to establish a place where women felt safe and comfortable and where their work was able to be displayed.

SD: Yeah I’d like to add a little bit about Véhicule. As Nancy mentioned it had been a club, and we didn’t know what kind of club it was until we did a book on jazz called Swinging in Paradise. At the back of the book, the author had put where all the old jazz clubs were. We realized that all these years that the Véhicule art gallery with the press at the back of the gallery that we had been working in this club called the Café Montmartre- a very popular place in the 30’s, a sort of a Blind Pig too I guess in the 40’s.

So we then understood the architecture of the place with the huge tall ceilings and the lodges, it was a great place to have an art gallery – which was an artist-run gallery.

We would arrive in the morning and we would never know what to expect. There would be all kinds of odd and interesting things happening at the gallery all the time. It was very diverse, it was dance, it was poetry readings on a regular basis, it was a pretty exciting place for us.

We were printing a few things ourselves, our own publications, but we ended up being the printer for a lot of the small literary presses in Montreal. So we know about a lot of stuff because of that. It was sort of what was passing before our eyes. In fact, in 1976, we did a little catalogue, and in that catalogue I noticed that we became the so-called distributors of about seven or eight little literary presses, presses like Cross-Country Press, run by Ken Norris, Jimmy Lee and the third person I can’t remember. So we printed little books for them. Here’s a lovely little book called Some of the cat’s poems by Artie Gold, one of our favourite writers.

NM: I think it’s worth saying that at the time it was really, really important to people and the arts scene generally, to be very multidisciplinary, this idea of breaking down the barriers of who was a visual artist versus who was a writer or stage presentations or whatever and there was a tremendous movement to think about the arts in a much broader kind of way and that’s why the gallery had poetry readings and it was an attempt to really mix things up. I think it was fairly successful for a good amount of time. There was dance and all kinds of other things that were going on all at the same time in the same places and there was a lot of cross-fertilization between the arts.

SD: You know what, I didn’t see that happening, there was tremendous artistic activity across the country, but I think Montreal was very different in the sense that you had this diversity, right from the get go. And because we were printers, so many people passed through us with printing jobs within the arts community, one way or another: posters, catalogues…

LR: You would do posters as well for these bands?

SD: Yes, and for the events of art galleries and it sustained us when weren’t on employment insurance or some other acronym it was back then, off and on. It was hard to make money, but we managed to do it. We also had great relations with our colleagues, with other printers in the city, we did a sort of alternate printing, one was Press Solidaire, the Marxist-Leninist printer. And they had bigger presses than we had so when we couldn’t do a certain job, we would run it off to their press. The really interesting thing with them is when the 1976’s Olympics were going to happen, they were concerned their printing plant would be raided by the RCMP and decided to close down. They didn’t want to be damaged in any way and maybe that was paranoia or whatever, and so for three weeks before the Olympics, they closed down and sent all of their customers to us. Which was wonderfully bizarre because we used a whole lot of red ink! It was a really interesting time as we were sort of the non-sectarian press in the city then.

LR: For the most you were printing English publications or did you sometimes print French ones?

SD: Well, we worked with Lucien Francoeur, we did a translation of his work and I loved when we showed him the book and he went: Oh my God! It looks so American! He was so happy it looked American– we didn’t see it as looking American but anyway. I actually have a… it’s not the one we printed but I just thought it was really neat book published by Les Herbes Rouges by Lucien Francoeur called Snack Bar, it’s really interesting when we look back – this was the 70’s – it’s sort of as much French as it is English. So he was really experimenting.

LR: Well, the sense that what we’e looked into so far with this project but also from myself of being a veteran of sort of the early 80’s, the underground, the DIY press scene, the two solitudes are a little less present because I don’t think they could afford to be so separate when we’re basically very small and I am just wondering to what degree that was the case there too that there might have been some cafes, hangouts, and poetry readings with poems in both languages… what was the situation back then, how much intermingling was going on?

SD: You know it’s funny because in a certain way – at least from our point of view, from our presses – there is more mingling now then there was then. Not that we have more money now and that we can exchange rights with our francophone colleagues but it just seems that we were very wrapped up in our own little scenes and sometimes there would be some crossover but not a heck of a lot. On our part as a printing company, a cooperative, we had that kind of exchange; we would do favours for each other. But generally speaking there wasn’t a lot I don’t’ know what’s your experience Adrian?

AKE: It was an extremely small community, which was a plus because you knew everybody. If you went to Véhicule readings, you could know all the English poets in Montreal. The extraordinary thing was that all this flowering seemed to happened all at the same time. It was right then in the early 70’s. I brought a magazine produced by Raymond Gordy, this is from December 1972, again poems stapled, it’s called Booster and Blaster, and the idea was that if you were a Montreal English poet, you could easily be published in there but the back of it, interestingly enough, carried criticism. So you’d have other poets criticizing poets’ work, and there is a declaration in here at the beginning of what they are up to as if they have a sense in 1972 – this is before the Véhicule readings – that there was a flowering about to take place and that they were starting off by making a declaration which I am going to read to you. This also reflects on the English language community feeling like a distinct minority. So this says: – it’s headed:

“The English poets in Quebec today – The Montreal Free Poet Booster and Blaster publishes Montreal poets only, a very distinct community. There is a reason for this. We are an English-language, English-speaking community physically circumscribed within a larger French-speaking community. but paradoxically a community which shares a majority English-speaking consciousness. This is difficult politics and should create a poetry of meaningful content and commitment. This is in a sense a beginning. Too much poetry is also a criticism of the rest of English Canada. Too much poetry in English Canada is a poetry of experiences, a recording without reflection. Here in Quebec, that approach is unacceptable. We are going to be special. Here great English-speaking poetry will be written; not only confessional but historical, dealing with Quebec’s distinct and local reality survival.”

(read the rest of the passage in our scan of this publication on our image blog here.)

I think that’s something passed away but definitely, English-language poets felt like a community, and they were going make a stand, and it was going to be good.

NM: I think overall people were aware of each other but it was not, there was some interaction but I don’t think there were a lot of shared projects. They were certainly some translations and at that time we tended to do face-a-face where you publish the English on one side and the French on the other, which is not very popular at all anymore. In fact, any kind of bilingual publication is considered a kiss of death at this point.

LR: We still see some here at Expozine although not a lot.

NM: No, it’s considered a marketing nightmare because neither community likes it apparently. I don’t understand why but that seems to be…

LR: What the smart ones are doing now are wordless comics and zines, but this would only apply to more abstract material.

NM: I think there was great awareness between the Anglophone and Francophone communities but I think people were very busy with what they were doing and tended to be more within their own community.

LR: But the resource sharing again like the occasional printing was similar to what it is today I guess. I mean when you are too small to be completely separate then…

SD: Absolutely. There is one printer I would like to mention, Chez Ginette Nault. She and her husband were just incredibly unique people who I brought one book I think is a spectacular book and it’s…

AKE: The book is so good that we both brought a copy.

SD: It’s In Guildenstern County by Peter VanToorn, who was just a phenomenal poet. This was printed by Ginette Nault and it’s done in colour; they did really lovely work, and they did a lot of English poets.

LR: To this day, a lot of our regular (Expozine) exhibitors have printed with her up until… I think she might have packed it up about two years ago…

SD: Is that right? That is incredible. Yeah, I think she must be of a certain age.

LR: What about the… October 1970. From what I understand there was a lot of opportunistic rounding up of folk, did that touch on anyone you know like authors and poets? Any creative types on the Anglophone side, colleagues that you knew from the scene, caught up in any of that?

SD: It was mostly… it happened to our friends, mostly political friends and friends who were in the media who were picked up. But not too many poets. It’s a shame! They should have. No, it wasn’t the literary types.

LR: Another thing I wanted to bring up is how we see a continuum from the 60’s in a way, the idea that we are seeing today at Expozine, has roots in practices like cooperative presses, working together for events, promotion, posters and sharing space.

SD: You are right, because I think the diversity that we were talking about when we were describing the scene in the 70’s in around Véhicule art gallery, I think Expozine is quite unique. Somebody came by our booth today, at our kiosque saying that they’ve been to one in Toronto and it’s just a totally different tone, and I think you have the same kind of exciting cultural tensions and achievements that you have here.

LR: Just to verify while you guys are in the room, what about the Beats in the 50’s? Weren’t people putting out small press of published works in the 40’s and… I’m trying to think the community and the practices that evolved in your era or in the mid 60’s to mid 70’s are more the ones that led to what is happening today? I know you only came to Montreal in the mid 60’s. Was there anything similar as far as you know before that?

SD: You had Louis Dudek and Irving Layton, they were tremendous and there was the McGill 490 Review and there was…

AKE: The whole modernist movement started with Louis Dudek and Irving Layton and that was a period of huge activity, obviously prior to this but I think that there was a gap. One of the central figures here was Artie Gold, infamous Artie Gold. In the late 60’s there were poetry readings, huge poetry series at Concordia which you know, just prior to this made a big influence and George Bowering was there, and the Black Mountain poets would come and read, huge names from the States and that made a big difference and influence on Artie Gold.

NM: Incidentally, these are available at the Concordia Archives. There was a tremendous program when the Hall Building was opened in 1966. It was one of the first university buildings in Canada that was, at the time, wired. It was wired for audio and video and they recorded almost everybody who came to the university. A lot of those things have survived. We did transfers of many things from audio and videotape. There is still more to be done but there is a lot of it, which has been done, and those materials are available for consultation at the Concordia Archives.

LR: One thing I find interesting is when you talk about zines or fanzines — most likely a word that did not exist when you guys were talking about small press publications, or I guess chapbooks perhaps would have been the word used then. But when I see a mix, such as DaVinci which is a mix of different artists, graphics, poetry, abstract writing, collage, all mixed together and printed independently –that’s what we would call a zine.

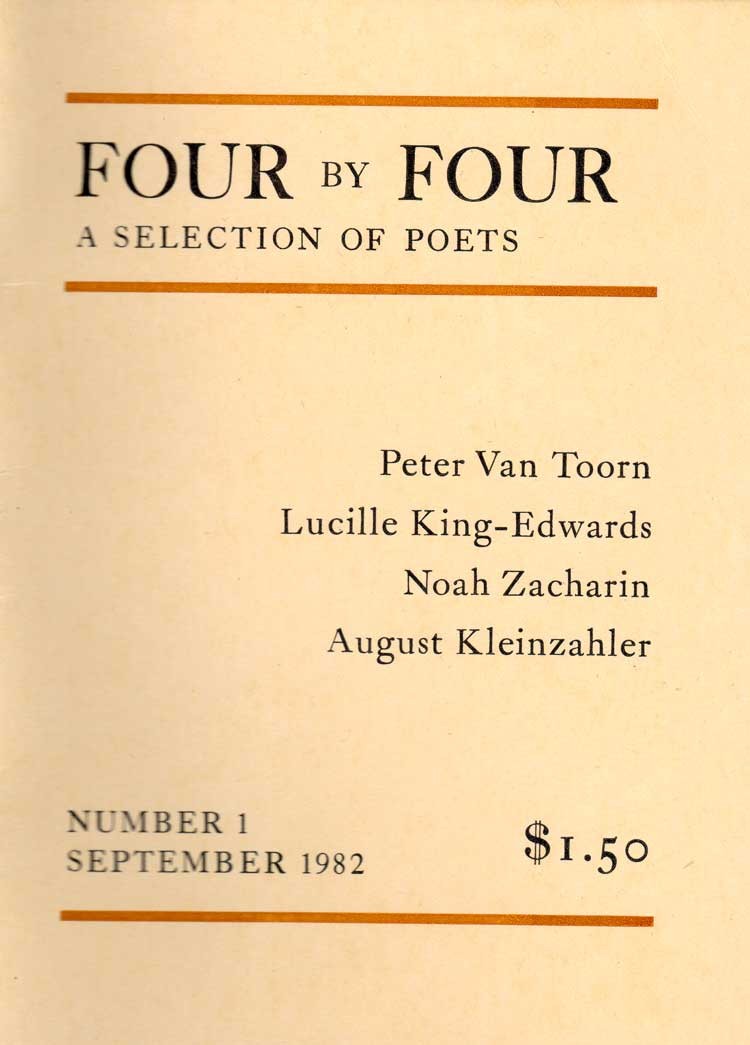

AKE: There are a huge variety of things. This was again my friend Fred Louder, who produced a little monthly zine, magazine, periodical, which was 4X4. So we would have four local poets with four poems each. And this would sell for $1.50. Very attractive. It is actually quite a collectible because August Kleinzahler is in it, and he’s become a very important poet in San Francisco.

A lot of these magazines or periodicals would attempt to give community information, when the readings were, you couldn’t Google all that kind of stuff, you had to get it from something like this.

SD: These are my examples. I love show and tell. These are a series of… when you think about them, they are very slight, they are eight pages with a cover. Very simple design, they were called Quarterbacks, sold for a quarter, designed by Glen Siebrasse, who actually designed books with Louis Dudek as part of DeltaCan. He became Delta (I think), and we printed his books under the name of New Delta. He was kind of a shadowy figure, whatever happened to Glen Siebrasse? But these books are lovely, these were printed in 1970. So that’s pretty early. And as you can see there are a lot of equivalencies to today (holding up the zine).

LR: We already talked about the fact that you had a offset press or a Gestetner press that was used, I don’t know if there were any risograph multicolour, that’s all the rage today, quite a few exhibitors printing on that at Expozine today. I am curious about where these were sold? Was it much like somebody would have to do today to publish their own zine, aside from putting it up on the web which wasn’t a thing then, so going out there on foot having a circuit of small stores that were accepting consignment? Magazine stands or news stands?

AKE: There were three basic places: The Word, of course the Double Hook, Judy Mapple’s store, she’s a huge supporter of local poets and another huge supporter of local poets, Mr. George at Argo and went back way before I was there.

SD: And the Mansfield Book Mart. You’d find them on the bottom bookshelf collecting dust.

AKE: Yes, when Jack Cannon was there. So I guess four places.

NM: But aside from this, certainly for women’s publications, which there were masses of small publications on all kind of women’s issues, some of them literary, some of them not literary, many of them not literary… You just got them wherever you got them, you went to an event and there were publications being sold. People sold their own stuff. They picked up the things, you went to New York and you might come back with 50 copies of something or you went to a demonstration in Boston and you found stuff, it was just everywhere. The stuff was just all around you. At all the events you went to, people you knew, it was very underground. The women’s publications were not being sold in bookstores anywhere that I know of.

LR: Or maybe at resource centers like Heads & Hands or something like that?

NM: Yeah, and the women centre which opened on Saint-Laurent, it was above where the Charcuterie Hongroise is today, that was where the first women centre was and certainly we sold publications there. I can’t remember where we got them. We just had them. And there were events, and at these events, these publications were sold. People would get together for common cause (a protest or discussion or concert) and at all these events, they sold these publications.

LR: Do you recall seeing Logos Magazine?

(all participants) Oh absolutely … Yes …

LR: Because that’s one that we found, over the years, quite a few copies of because I guess they printed large amounts. Aside from Mainmise on the Francophone side, were there any other similar high-run magazines? We are talking about 10,000 copies newsprint, large editions of these that were practically given away, I think for the most part they cost a quarter or something… I’m not sure what to call it, almost a general interest underground publication because you had some politics, you had some literary content, you had some graphics and of course, underground music kind of mix. Were there any other as prominent or are these the only ones?

SD: I think you have a couple of them on the wall from Logos. I can’t think of any other ones but I probably just don’t remember.

NM: But the university newspapers also had literary supplements.

AKE: The (McGill) Daily was very active, very involved with the community, and there was something called the People’s Yellow Pages.

SD: Actually Juan Rodriguez, who occasionally writes musical columns for The Gazette, back in the mid to late 60’s he put out a magazine called Pop-see-cul. It was before Crawdaddy Magazine, it was before the big magazines like Rolling Stone and we actually published I think the last edition of it. But it was a mixture of poetry and what was happening in terms of music and rockstars coming to town or jazz musicians.

LR: So that kind of publications where, it’s a little bit more like the general interest zine that covers a bunch of disciplines, available in more locations than the more literary material you are mentioning like for example were there underground record stores where you could also get some of these things or head shops as they were I think called. Where would one go for something like a Logos or Pop-see-cul or was it the same as at events like you mentioned?

SD: Phantasmagoria on Park Avenue.

AKE: Phantasmagoria was a major scene.

LR: Did the Yellow Door or the New Penelope or any of these places actually also sell books or magazines at the counter?

SD: No. The New Penelope was exclusively music.

LR: We don’t want to go too much further but we got about 10 minutes, I wanted to see whether there were some questions.

Questioner (Professor Will Straw): This might be most pertinent for Simon and Nancy: these days you wouldn’t do anything without getting a grant first (laughter among the panel)—was there anything in the way of government money floating around in those days?

SD: Well, as I may have referenced earlier, whatever acronym provided some kind of cash, one way or another, we used it. Because despite that we had all this equipment, we were renting out the space at a very low cost, we still needed to eat. So we’d go on and off unemployment insurance. There was a project called the CYC, Company of Young Canadians, which to this day I don’t really know what it was all about –except that you could get a “subvention” of some sort, to keep us going. There was LIP, Local Initiative Project grants. We would go from grant to grant or unemployment or whatever and supplemented by the (print) jobs we did.

Will Straw: That’s interesting because we know the artist-run centre movement before it was getting specifically arts funding was getting these “young” grants and unemployment insurance to develop. It’s an unexplored history of sorts.

NM: For sure, all these programmes were major subsidies. A lot of people also worked in the libraries at Concordia – the Sir George library was full of writers and artists and dancers

SD: And draft dodgers.

Nancy: Lots of people who were involved in political movements of all kinds, and for sure, people went and got jobs that enabled them to eat so they could do the other things that they did. I ended up in the Concordia libraries and then the archives – you just have to eat. Somewhere along the line.

LR: One theory that somebody we interviewed previously for this project had come up with was that after the October Crisis died down and the whole FLQ era kind of came to a close, that there was a sense that they “better keep the hippies busy”, a lot of government programs started up—somebody mentioned Radio Centre-Ville (CINQ) was set up, they received more resources than they knew what to do with, hired 20 people or something. That there was a lot of that. Then again, that’s just an anecdote, it sounds a bit exaggerated but obviously there was funding of various sorts – maybe it was also the recession of the early 70s, might have been another reason to start such programs.

SD: Then again in the mid 1970s the economy was doing pretty well, people didn’t think twice about quitting their job and saying “I’m just going to hitchhike to Vancouver” or whatever. As Nancy mentioned, at Sir George Williams (now Concordia) you had a huge number of draft dodgers and people who were working there because they came to Montreal because it was a place where you could get a job, that was like not bad work.

I also have to mention that there was an efflorescence of literary presses right across Canada in the 70s. If you look at us and Turnstone Press out in Winnipeg …

NM: But it wasn’t just literary—it was dance, it was theatre, it was music, it was across the board. I can’t emphasize too much the desire, the will to really integrate the arts in a much more basic level than we saw before — and that we’ve seen since.

LR: Would any of you say that the sheer numbers of the baby boom generation that created one of the largest generations of young people –

NM: Educated young people …

LR: Educated young people had to do with this efflorescence, this desire to be so involved ….

SD: Well, yeah, for obvious reasons, because of that, the Word, the written word, was very important in terms of the written stuff. The previous presses in Canada in terms of pioneers of the modern presses were things like Coach House Press, Talonbooks out on the west coast that started in the 60s, but there weren’t a lot of presses. It was really in the 70s that you had from coast to coast all of the other arts and publishing houses.

LR: In terms of cost of living, you mentioned a little bit earlier about how you were able to get an apartment for $100 a month, a storefront for $175 and so on. Of course wages were lower but from what I’ve heard so far, it was a lot easier to get by, you didn’t have to spend half your income on rent, you may have been able to pay rent after a few days work or what have you.

SD: I think every generation says that, though (laughs.) We were in fact paying forty two dollars for our flat on Clark St., then I rented downstairs too where I had my studio since I was a painter. So in total it was eighty two dollars a month … y’know.

LR: But this did help in keeping people able to create so much art and get involved…

AKE: To reflect on that a little bit, we weren’t terribly concerned about finances. Now, was that a function of being young and y’know … But we used to close for all of August, go to Vermont. (laughs)

SD: It was a lifestyle (laughs).

AKE: Yeah it was.

LR: Of course you’ve been printing all this time, not anymore on presses that you own but to discuss briefly the economics of it on the production side, how affordable was it when you were running your own presses compared to the digital printing today, and putting out these perfect bound books. Has it gotten harder, more expensive, does it take more capital to print today compared to then or has it remained relatively stable?

SD: Well first of all when we did our printing back in the 1970s, we printed from 1973 – 81 then we took over the press editorially without having printing presses. We used to print on paper left over from paying jobs. We would save that way. I think because we’ve become a little more mainstream, when you get a distributor and you get your books out there in a certain way, it’s still expensive but the fact that you’re getting books marketed and sold means that you can afford the printing costs. I don’t know if they’re higher or lower but the fact is that you do have some sort of cash flow.

NM: And the technologies changed – you can’t do that kind of printing anymore. The presses that our printer uses cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Our small presses were great for small runs but they can’t do the larger runs, and the technology is just totally totally different. On the other hand, our daughter is back to printing on a letterpress Heidelberg. So who knows …

LR: Well, this year after a few years going to digital printing, we printed the Expozine programme on an offset press. But we visited their production and all the pre-production is digital, it’s not your grandfather’s offset press. But artisanally, there’s definitely a big trend that we see here at Expozine today for the old printing methods. Another question?

Q: Was it prohibitively technically or financially in the late 60s to publish novels, like big bricks, or was it possible.

SD: Well maybe because I was a failed poet myself, we were mostly interested in poetry and because we came out of an art gallery, we did a lot of artist books too. But we weren’t interested in novels. Were people writing novels? I guess so, I’m just not aware of it.

NM: I guess they were going to the publishing houses. It’s the same issue around the art galleries – the mainstream art galleries were putting on mainstream art shows, and that’s why the underground galleries started. But it would have been very expensive for a small publishing operation of any kind to do that, and the chances of success were just so low that the outlay might have broken the bank.

LR: Was it more on the binding and assembly side for a novel, because I guess the paper might not have been an issue for a press.

SD: We only did our first real large book in 1980 and we had started in 1973. We began doing literary criticism. But I think we saw poetry as being perhaps not mainstream and that was one of the reasons why it was very appealing. It didn’t make any money of course.

ND: It was never about the money.

LR: I’m sure poetry is not any more mainstream right now…

SD: No, no it isn’t.

LR: It might be going through a bit of a rough patch at the moment, in fact. Another question?

Q: I just wanted to ask if you could clarify with a couple of examples of what you would consider mainstream in the late 60s.

SD: Hmm, perhaps Ryerson press.

AKE: Well you’d look at Toronto and look at the mainstream presses there. Ryerson Press, MacLelland & Stewart, that was the mainstream. There was always a sense as I read earlier, Montreal is different, the centre of civilization is Toronto, but we’re gonna be better. So I think the mainstream was very much there.

LR: That’s funny, there was a panel yesterday about the music scene, and the exact same point came up, the question is why is it different here. In the 80s there was a saying that here there was a community, ready to experiment and do different things, and in Toronto there’s a business.

Q: Would the experience you had especially from the early seventies when you came onto the scene, how much of the books you published or printed through the years would you consider to be vanity projects, vanity books, versus say a commercial book that someone was trying to make a living as an author.

NM: But vanity is not … I think the way you’re describing a vanity press is not the way I see vanity, it’s more something that you’re publishing yourself, you’re paying somebody to publish something for you. The publishing house has not necessarily made a choice. You’re paying somebody to put this book out for you, as opposed to a small press – we never published anything that we didn’t want to publish. (laughs) And we’re not rich!

SD: However, you always had writers who published themselves in various ways, they’d form a little press and publish their own work. I mean, that’s happened since I think we had the printed word. We had to form of editorial committee in 1977 so we could receive funding from the Canada Council. So we just created one – it was three poets, Endre Farkas, Artie Gold and Ken Norris – so they published themselves and a lot of their friends, and I’m not saying that in a pejorative way. It’s just what literary people did – it happened in the generation of Irving Layton, Louis Dudek and the whole gang. And you know, they published Margaret Atwood because they liked her and nobody else knew her. Y’know, I think it happened more that way than “vanity.” Perhaps there was a similar goal to get your type of writing out there in the world…

Be nice to hear more about Mr George, about the other bookstore competition: from Mr Heinemann at Paragraphe Books at the corner of Mansfield and in the basement then and Penelope working at Cheap Thrills on Bishop near the Hall Building and Kurt in Cafe Prague. Or even an earlier bookseller Bicycle "Bob" Silverman with the Seven Steps between the Y, the Sir George Williams Norris building and the Stanley Tavern, all three opposite the Pam Pam.