Artist Erik Slutsky on Montreal’s 60s – 70s music scene

Erik Slutsky is a longtime Mile End native and veteran visual artist, who we met through his hosting of the New Penelope Facebook group – a group that since 2013 has become a lively place for nostalgia about the 1960s music scene, centered around the legendary venue. He kept his copies of old New Penelope Café newsletters, concert posters and many clippings about the wider music scene of the time, material which helped kick-start the memories as the Facebook group took off in no time. We chatted over a couple of summer afternoons about his experiences growing up in Montreal. I asked him about what it was like starting a band, seeing all those great shows and seeing the city change from the mid 60s to the late 1970s.

ES: Being a kid was a lot different then, a lot different. As a little kid (in the 1950s) I took my bike everywhere, we took our bikes to school and nobody worried about safety. Our parents, if they thought about it, we never heard about anything about it, we did whatever the hell we wanted. As far back as I can remember I had total freedom. If we were hungry we would just run into one of the kids’ houses, anyone’s, and just grab something from their refrigerator and eat, and then we would leave. And then we would go play again. No one ever thought of telling us that we couldn’t eat their food, it just seems like part of what the kids did. When you think about it, this way the mothers didn’t really have to take care of their children during the day, because we were out all day. If we weren’t in school, we were out playing. We didn’t hang out and do homework for hours and hours. Life was good. Simple, cheap, safe, fun.LR: Was high school the same as it is today? Secondary 1 to 5…

ES: You stayed in elementary school until grade 7, then you did four years of high school. I feel sad for kids to have to spend five years in high school, because high school was not a place you wanted to stay very long, you wanted to finish and get out of there already. When they took a year out of primary and added it to high school, I was like: poor kids, five years in a high school? What a drag. It’s a pretty big age difference, it’s kind of a strange mixture of 12 year-olds and 16 year-olds, you don’t exactly get along.

LR: Were the school boards divided?

ES: It was Protestant and Catholic.

LR: But you were of Jewish extraction.

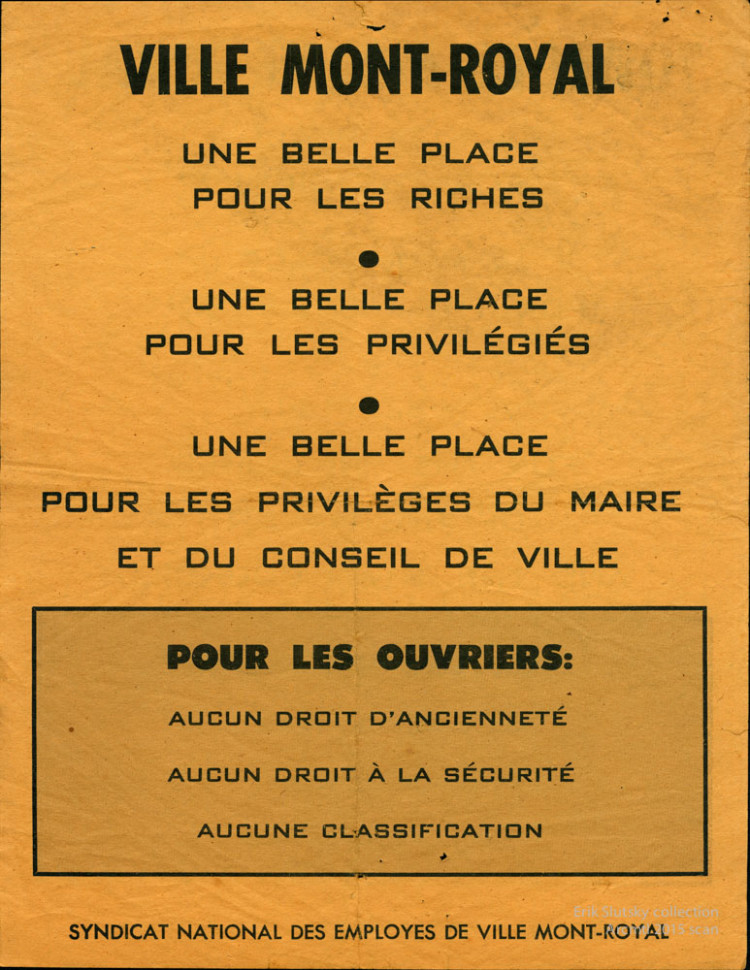

ES: Right, so I went to Protestant school all my life. You couldn’t go to Catholic school, they didn’t accept Jews. I didn’t even know any Catholics. Everyone I knew was Protestant, except for the few Jews in the schools I went to, which is the reverse of my parents, who went to Protestant school but everyone there then was Jewish. But they went to school around St-Urbain, although they were protestant schools, something like 90% of the students there were Jewish. But where I went in Town of Mount-Royal was exactly the opposite. We were maybe 10% Jews and the rest Protestant. So I just grew up with them, and sang the same hymns, said the Lord’s Prayer every morning.

LR: And no one batted an eye.

ES: Not until I was old enough to question what I was doing singing Onward Christian Soldiers. A lot of Jesus stuff I used to like singing just because I liked singing. We started with saluting the flag and singing God Saves the Queen every morning, then the Lord’s Prayer and then hymns and then school. I did that for years and years until I was about 13. Why am I singing about Jesus? Although I didn’t really care up until then because my parents didn’t follow anything.

LR: So your family was fairly secular.

ES: Totally. So one day I decided not to sing the Christian songs. I was told to write out the line 500 times as punishment.

LR: Oh my god, can you imagine the court case today, the discrimination…

ES: Yeah, it’s a whole different ball game. Unless you are living in like… Saguenay.

LR: Although now, parents sue schools that make their kids sing prayers.

ES: I think it’s going a bit too far because you know, we did it and we just moved on, we had other stuff to think about. The words meant nothing to us. If you were a religious Jew, you wouldn’t go to that school anyhow.

LR: I know you were also in a band fairly young, was it in high school?

ES: No, I started about 12 or 13. It was when the Beatles had become popular worldwide. It was a battle between the Rolling Stones and the Beatles, so all of a sudden our lives turned towards music.

LR: Was that right after Ed Sullivan…

ES: I already knew about them before the Ed Sullivan show, and like most kids, we were all waiting to see that show. I watched it with my parents. We watched it together, and later the Rolling Stones as well, which was completely shocking after seeing The Beatles… The Beatles looked clean cut and proper, nice boys and the Rolling Stones were seen as bad boys. For a lot of us, it kind of taunted us in two different directions. Do we like the sweet kids with the nice songs, or do we like the tougher guys with the more raunchy stuff? We kind of flipped between the two, you had your Beatles fans and you had your Rolling Stones fans. I had a Beatles wig, I actually wore one on the bus going to school– can you imagine?

LR: Now how quickly did that come about? People selling Beatles wigs …

ES: I think the day they played on Ed Sullivan, the day after, there were Beatles magazines everywhere, I bought Beatles magazines, I started buying my Beatles records right away, I also started buying Rolling Stones records as soon as I could. I don’t know where I got the money, I guess I got an allowance. Records were probably pretty cheap. I think Dominion stores were selling them, Dominion like Steinberg, had a record section. I think I bought the Animals record there at the TMR Dominion store. I bought the Beatles there, I also had a big collections of 45’s. Then I started playing in a band.

LR: Was any of this music on the radio?

ES: Not in Montreal. And we couldn’t pick up American stations. Records and word-of-mouth from friends and going to the record stores like Phantasmagoria, they would be playing stuff all the time, whatever was current, and I think you were able to listen on headphones there. Archambault started to do that a bit later.

LR: In the meantime, everybody would just sit around playing records and you would hear records that other friends had…

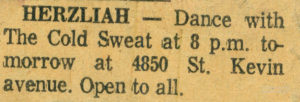

ES: Yes of course, and we would write the words down so we could sing the songs and stuff. The band was just for fun at first — we practiced in my parents’ basement, because they seemed to be the only ones who would allow a group to play. There was a drummer, and we had a Hammond organ, it had speakers with a fan in it giving it that special sound, which was pretty cool. A lot of bands were using that at that time. We had a bass player, lead guitar, singer. And then later we had a trumpet and sax when groups like Chicago, Blood, Sweat and Tears came out. My group played at my bar mitzvah, I still have it somewhere, it was filmed on 8mm. We were either called This Side Up or Cold Sweat, I don’t remember because we changed names at one point. We had cards, which we wrote by hand with our names and phone numbers. We played in my basement for neighboring kids. I had already started writing music already by the time I was 14. The band only played one or two of my songs but I did it for me.

The New Penelope started for me in 1968, when I was 15, so we must have been playing blues already by the time I was 14.

LR: Which high school?

ES: Mount Royal High School. My band played at the graduation. I remember Frank Marino (later of Mahogany Rush), who I went to school with, played a few tunes with us there. Between the ages of 15 and 17, we played most of the fraternities at McGill that would hire us, whether it be a Christmas party or some kind of frat party, where there was a lot of drinking and carousing going on.

LR: So those gigs weren’t concerts where people pay and sit and watch you play …

ES: They were dancing and drinking and talking. We got paid, not very much. Disc jockeys were not a big deal yet. And of course, even when they started it was not like DJs today, it was just basically putting on a record.

So we played at different schools for different events… a lot of churches would hold dances in their basements on the weekends, I guess they thought it might keep the teenagers off the streets or something. All the kids would get stoned anyhow before they went to the church basement, and nobody was searched so people brought in booze anyhow. And everybody was underage, nobody gave a damn. After high school we were off to CEGEP or University and had to make a decision: are we going to really try to make a career out of this? Because if we are, we will have to maybe take a year off school and work hard at it, we were looking at getting a manager and maybe do something more serious. Finally, the majority of them decided no, they just couldn’t give the time to make the music, so we broke up and sold our equipment.

LR: When you took the name Cold Sweat, I can’t help but presume that’s because James Brown’s hit was out at that point. Did you play any James Brown’s songs?

ES: Yeah, I think we did play one James Brown song, one of his big ones though. I remember more that later on in the band, when we finally got our horn section, we were doing a lot of Blood, Sweat and Tears type of stuff.

LR: Did you record anything?

ES: We did have an eight track Grundig tape recorder. But I don’t think I have those tapes anymore. The machine was in my mother’s basement, I think I trashed the machine and may have thrown out the tapes.

LR: No one ever copied the tapes or made any use of them?

ES: No I don’t think so. That was going to be the next level. And that was going to require time we weren’t willing to give. We were just trying to get a manager at that time. We got Sheldon Kagan. Donald K. Donald was already doing okay, so I guess he was working only with people that were being recommended to him. Kagen was still looking, so we had him come over and listen to us. We broke up like just a few months after that. And I think he did get us a few shows.

LR: Did you ever play any of these kinds of shows (holding up poster), at the Bonaventure Curling Club? Because they had 10 bands on the bill those days.

ES: We may have, but I am not sure.

LR: Were you too young in the heyday of these big all-day shows, way out at Côte-de-Liesse, or the Maurice Richard arena…

ES: I think Maurice Richard for some things. Bonaventure was in a kind of difficult to get area if you didn’t have a car.

LR: On this poster they showed the bus to take, the 16, which ironically is still the bus that goes through Graham in TMR. The Saint-Laurent auditorium, which is where I believe the CEGEP is, seems to have been a pretty busy venue.

ES: I remember going to a rock show at Vanier College at the back of the College. We either had an all-day or a weekend kind of rock festival, I must have been about 17 at the time and I had stopped using acid. Up until that point, dropping acid was a really big thing for about two years, roughly 1967 to 1969. By the time I went to this Vanier College thing, it was probably local bands like the Rabble playing. Vanier had a Red Cross tent set up, because a lot of people ended up with bad trips. I even volunteered to work for the Red Cross to help young people who were going through bad trips because I knew all about that shit. Some of my best friends experienced pretty traumatic hallucinatory effects from it, and after that I decided that I wasn’t going to take it anymore. I figured that I’d seen good trips, bad trips, if these kids are having bad trips maybe I can help a little bit. You just have to sit with someone and reassure them.

LR: I think that was the main thing is that you felt that you were permanently in this state.

ES: Yeah, there was that fear, because you lose all sense of time. Your mind just kind of floats away. We had learned from the most experienced acid users that the best thing was, don’t think about time. You had to empty your calendar and your schedule with any possibility of maybe having to go home for dinner, meet your parents or your grand mother or go to school. You had to have this big long space, maybe 24 hours, where you could kind of disappear and just let it happen. You could just lie on the ground, listen to music or whatever and just let this hallucinatory effect do its thing. If you fought it, that’s when you had trouble.

LR: I presume your parents had no idea about this at the time.

ES: No.

LR: Did you have any friends with hippie parents or hip parents, beatnik parents?

ES: No. When they first found out that we smoked marijuana, when I was about 15, 16 — it was just marijuana they discovered, but we were taking mescaline, we were taking speed, we were taking mushrooms, whatever we could get—but when they found out, their reaction was to blame a friend of mine, saying he was a bad influence and that I couldn’t see him anymore and that I should go see a psychiatrist. It wasn’t unusual then to hear how marijuana was the gateway to heroin. Basically, once the kids started to smoke marijuana, you were just on the road straight to the end. It seems ridiculous but I guess our parents were frightened for us. It just came across as a conflict of these two generations.

Of course, I never went to a psychiatrist. I said to my dad: Okay, I will go to the psychiatrist if you quit cigarettes. He couldn’t quit smoking cigarettes and I never went to the psychiatrist. And then somehow it just, I don’t know, they kind of liberalized a little bit.

I smoked pot for the first time I remember at 13 and then I probably smoked it everyday for the next five years. I was pretty much stoned throughout high school.

LR: Was it just around, or did you have to go and find a dealer …

ES: We had a dealer, he was the brother of a friend of ours. He was just a neighbourhood guy, 5 years older than us. We’d get hash and grass from him, we would usually buy it as a group, like we would each put in five bucks or something. We would go to the park at night and smoke, or usually we would smoke pot at recess in high school, that’s why I was stoned throughout high school. Yet it didn’t make a difference. I did very well in school– except that I would fall asleep sometimes in typing class, which was just after recess or lunch when we’d smoke. My head would collapse onto the typewriter, because nobody cared about the typewriting teacher. She didn’t seem like an important individual in the school. It’s not a nice thing to say, but that’s how the poor typewriting teachers were treated.

LR: I think it’s par for the course in 67, 68, I mean we are talking about the music scene, right?

ES: Yeah, and they seem to go along very much with each other. A typical break in the New Penelope was to go next door into the Swiss Hut, which was a bar/ tavern and we would smoke weed in the bathroom. At the urinals, each guy would pass a joint to the next guy, and often the guy next to you would be the guitar player for James Cotton or the bass player for Paul Butterfield that came for a beer during the break. You would go in for a beer, even if we weren’t old enough, it didn’t make any difference, you’d go in and drink one of the big beers and maybe have chicken livers in a basket, I think it was. The Penelope only had coffee. But the Swiss Hut was a dump.

LR: Was it like what we would call today an old man bar…

ES: Probably during the day, but in the evenings when there were shows at the Penelope, it was filled with people from the Penelope. So probably from 8 until midnight, they got a good crowd from the New Penelope. If there were old people in there, like I know now, 50 years later, they weren’t visible to us. As you get older, you get more invisible to younger people. They can look right through you, and I guess we didn’t even see them.

LR: Do you remember leaving at 2 in the morning or something from the New Penelope, what it was like: Sherbrooke and Pine Avenue, lot of hustle and bustle, or was it quieter than compared to today?

ES: I don’t think it was at 2 o’clock in the morning when shows ended though, because when I came home my dad would usually be up waiting for me. We would talk about the shows afterwards with milk and cookies. Probably was around midnight.

I have no idea why the New Penelope never had a liquor license. It sure would have helped him, (owner Gary Eisenkraft) considering that coffee was 30 cents a cup. And that was the only thing he sold.

LR: Did he at least have snacks– I mean, how else would you make money aside from the 3$ at the door?

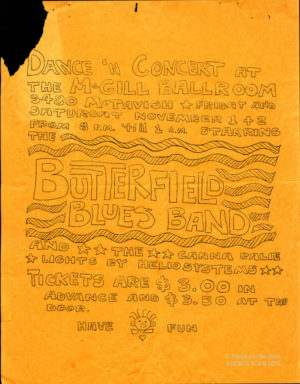

ES: Yeah, it was like $3 to see Paul Butterfield. The club only held maybe when it was full, 150 people or something? At most. So that would be like $450, maybe make a total of $500 or $600 in a night. What was he paying Paul Butterfield, $300 for a week for all of his musicians? I heard he was in debt when he closed. He was probably working for free and putting in his own money hoping I suppose at some point, something would happen. I wonder, did he want a liquor license? Did you have to pay the cops to get a liquor license?

LR: Sounds like a lot of the money was going off next door.

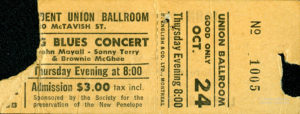

ES: Yes, because between sets could be a good 45 minutes. Sometimes bands would come back pretty drunk or stoned. I didn’t know anything about Gary Eisenkraft by the way until the Facebook group, when I found out a lot about him from guys a few years older than me. I can’t believe that a guy as young as he was was able to pull off all this stuff. To get all these people there (pointing at the posters.) The musicians that went through there had a huge influence on the city’s musicians, both French and English. I found out that a lot of French people went to a lot of those shows. (Looking at a ticket for a John Mayall, Sonny Terry – Brownie McGee show)

ES: Yes, because between sets could be a good 45 minutes. Sometimes bands would come back pretty drunk or stoned. I didn’t know anything about Gary Eisenkraft by the way until the Facebook group, when I found out a lot about him from guys a few years older than me. I can’t believe that a guy as young as he was was able to pull off all this stuff. To get all these people there (pointing at the posters.) The musicians that went through there had a huge influence on the city’s musicians, both French and English. I found out that a lot of French people went to a lot of those shows. (Looking at a ticket for a John Mayall, Sonny Terry – Brownie McGee show)

The Student Union was a pretty wild place. The McGill Ballroom too—I found out later that one of the McGarrigle sisters or both were involved in the light shows at the McGill Ballroom. They used to have these slideshows and light shows, which went along with the LSD situation at the time because everybody was tripping.

LR: As far as weed smoking, did it never happen at the Penelope?

ES: No, never. I never remember anyone smoking.

LR: But it was a smoking venue, you couldn’t have a no smoking sign for cigarettes I presume?

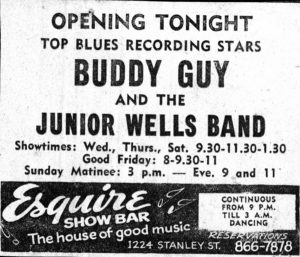

ES: I guess there was. I wasn’t a smoker at the time and it’s funny how there’s certain times when people can actually ignore people smoking. It sounds crazy today. In the sixties, everybody was smoking. It must have been pretty smoking in the New Penelope I imagine, I do remember going to clubs where you basically walk in to a cloud of smoke but we just didn’t realize it. I used to go to the Esquire, on Peel near Ste-Catherine. it was a pretty cool place.

LR: Was that a mixed crowd?

ES: Yeah, it was.

LR: Because I guess at the time, the black communities would have been below Windsor station, near Bordeaux, where Rockhead’s was on Saint-Antoine,

ES: Unfortunately, I never made it to Rockheads. I did I see Little Stevie Wonder in one of the clubs. He was called Little Stevie Wonder back then.

LR: At the Esquire?

ES: I think so, or maybe the Hawaiian Lounge. I discovered the Esquire at the end of the New Penelope era. It was a classier place, it had a sort of New York night club kind of feel to it, and it was obviously run by gangsters, or it seemed to be, which made it all the more attractive in some ways.

LR: Was it similar to the New Penelope, 150, 200 people?

ES: No, bigger. If I remember correctly, there was a dance floor and tables and chairs. You could order drinks to your table, which was pretty classy for us after the New Penelope, where you sat down on benches with a wooden board in front of you where you could put your coffee down. Not that we cared.

ES: No, bigger. If I remember correctly, there was a dance floor and tables and chairs. You could order drinks to your table, which was pretty classy for us after the New Penelope, where you sat down on benches with a wooden board in front of you where you could put your coffee down. Not that we cared.

There was also a place called George Soroya’s Hawaiian Lounge, that’s where I saw Stevie Wonder, I think. It was almost the same as the Esquire show bar, it may have been on the same street or the same area, I don’t know what happened to that place.

LR: There was also the Kon-Tiki on the same street,

ES: I use to go at the Kon-Tiki a lot with my parents.

LR: I see on the list of shows you kept at the time that you saw Muddy Waters at the Esquire, were you 18 yet by then or would they just never card people for shows?

ES: No, I think they did card at the Esquire. I might have been 18. James Cotton I saw him in quite a few times. And I did become a bit of a harmonica freak; I still have a couple of harmonicas.

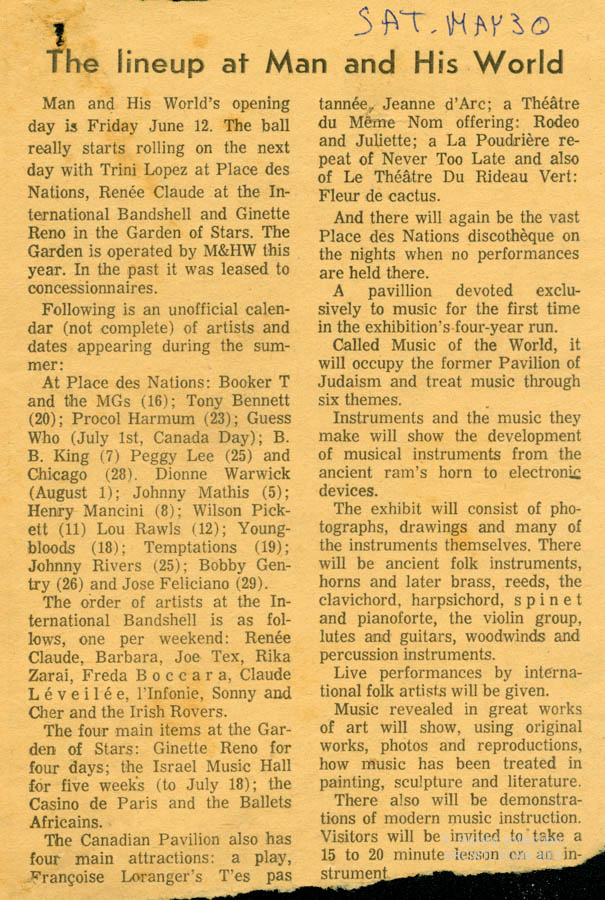

LR: I also see a lot of bands at Expo 67 on your list.

ES: I went every day in the summertime. I was 14, I had a passport which was good for the whole fair, I don’t remember how much it was. There was enough to occupy you all day, visiting different pavilions, and there was tons of junk food so we’d eat our brains out.

LR: Expo must’ve been like a big playground. I am assuming it was very bilingual.

LR: Expo must’ve been like a big playground. I am assuming it was very bilingual.

ES: Hundreds of thousands of people a day were visiting, I was there when I think they had the the most people, I believe it was 400,000 people in one day. It must have been a very mixed crowd.

LR: I haven’t really asked but just assume that growing up, you felt a part of the English community?

ES: I didn’t feel part of any community, but I was obviously part of the English community, as there were just no French people where I lived.

LR: How did you learn French later on?

ES: They taught it very well in school. Extremely well. They taught it by rote. We had to memorize everything, the grammar, starting with avoir et être and memorize all the different passé composé, impératif, futur, présent and then we would just memorize it. The same way we learned math 2X2=4, 4X8=32, I don’t have to think about it, it became embedded and melted into our brains. Once we learned the conjugation of verbs and we started to learn how to use the nouns and whatever correctly within a sentence, we learned it pretty well. The only problem was we had very little opportunity to use the language.

LR: That’s what I was going to say: how do you keep the French then?

ES: I didn’t until I kind of had to relearn it, that base was still there by the time I moved to France for two years, in 1973 or 1974, so I was 20 or 21. I went to a French art school there and was the only English-speaking person. I became totally immersed in the French culture, and strangely enough I had never been immersed in it here in Montreal. Once I came back, it was easy to know connect with the French community, they made fun of my French accent when I came back here. I lived in the South so it was a Provencal accent. In my twenties, I started to connect with French people and moved to Mile-End which was multicultural at the time, you know, Portuguese, French, Greek, English, it was a bit of everything. And often now, I’m stuck in these situations where I may be the only Anglophone. I don’t understand everything that goes on because there are some phrases that I am still learning and my learning curve is pretty flattened out at this point in my life, but most people say to me: Oh, you speak French very well. As long as you do the best you can, they will usually switch to English if they know you made the effort to speak French. That’s why I could never understand these English-Rights groups.

LR: If the point is to preserve the right to live in English only, in Quebec, I think that’s ridiculous. That’s the same as any hardcore separatists who believe they need the right to live and do business in French only, ever.

ES: To me, the thought of being an English-speaking person who lived in this city your whole life without being able to speak French is beyond my comprehension. I am very, very, very happy to have a foot in both worlds, and get the best of both. And of course there is much more going on in the French community in Montreal, in terms of the quality of the culture, than in the English community. For instance, I like theatre very much, but the quality of English theatre is nowhere near the quality of the actors in the French theatres. The French actors in Quebec, they have the opportunity to practice a lot, to do TV, to do theatre, to do movies, talk shows, they can work and they can hone their craft, whereas the English artists, actors, don’t have that opportunity, they just have the Segal Centre and the Centaur. I just recently went to the Centaur, and I was very disappointed. And I went with a French Canadian woman… The writing was of a mediocre quality. The acting was also mediocre. I was in fact a bit embarrassed with the woman I went with, because I have gone with her to Théâtre du Rideau Vert, Nouveau Monde, you know, good theatres, and seen stuff really as good as you can see probably anywhere in the world. This just didn’t measure up. It was sold out, but when I looked around in the theatre I thought: I don’t really want to be a member of this club. Because it did seem like a private club in a way.I don’t want to be lost in that bubble. That’s what I like about living in the the Mile-End, the Plateau…it’s really nice to be able to have the opportunity to experience a lot of different cultures, it’s just a wonderful part of living.

LR: Do you feel like that’s something that you saw change in Montreal– before you went to Expo 67 every day that summer, I’m guessing that Montreal until then wasn’t exactly the most multicultural place. Then by the time you came back from France, six or seven years later, it must have felt like things were changing?ES: Well up until a point, up until I’d say the first referendum, that was 1980, I guess, the main thing was you had English and French. We didn’t talk about the Muslim community or the Black community… Now we have a huge Arabic community, huge French from France community, gigantic South Asian community… all of them have introduced their cultures and as they built their wealth, their influence grows outside of their community. For instance, the Filipino community, which began small as a bunch of ladies taking care of their children and housekeeping, over the past generation or two, thank goodness, have been able to bring over their husbands and children. Fortunately many have been able to move out of just that trade, and of course, next was being nurses and things like that, opening restaurants and businesses and then, their impact starts to move out of their community and that’s great.

LR: You saw that in 1974, 1975, 1976, in Mile-End …

ES: Mile-End was in decline in the 70’s.

LR: So a lot of Polish, Jewish and Greek?

ES: No Jews. In Mile-End in the 70’s? The Jews had left Mile-End. There were a lot of Greeks. There was starting to be a lot of Portuguese, a few young people like me because I had a place on St-Urbain at 23. I didn’t realized it as much at the time, but for the next 10 years or so Mile-End was in a real decline. A lot of buildings were being burned down by landlords, rents were ridiculously low, businesses just didn’t work, it’s difficult to think about comparing to what you see today but you know, Brooklyn went through the same kind of cycle.

It had started a lot earlier in Mile End. In 1954, in the area bordered by de la Savane, Victoria and Jean Talon, they built 500 houses. My dad and many of the people from St-Urban Street and Clark bought all the 500 houses in one day. All you needed was $500 down. They all borrowed money from somebody else, put the $500 down and then it was like $39 a month mortgage for 25 years or something like that. The house was $12 500.00. So they all sold in that same day, and it was all guys who knew each other from the old Jewish neighborhood. They all had their first kid around 1953-54 and most had another one around 1957. So I had 500 friends, immediately.

That was the first move out of the old area, everybody had been in the Plateau – Mile End – Outremont until 1953, then they moved out. But by 1967, 68 I had moved back here.

LR: Did your parents find that to be strange at all, when you moved back?

ES: No, my dad loved the old area. There was nothing like it where we lived, out in Western Montreal. They built it all out of nothing, of old farmland.

LR: I got that after first moving near downtown from St-Laurent. Both my parents had grown up near downtown and thought I didn’t appreciate what an improvement the suburbs were: “We go and leave the gritty alleys for a nice lawn and everything, and you go back there!”

ES: A lot of parents said that to the kids back then. It was like a grandmother saying to you, “What, you ripped down the plaster to expose the brick wall? I left a shtetl (city, in Hebrew) made out of only bricks and now you want to have just bricks?” Or, “you stripped all the paint off the rocking chair? To expose the wood??” There would be like 70 coats of paint on the rocking chair, they had spent years painting things so they would look new every year. Anyway my dad loved the neighborhood. The people who grew up there had fun there, they liked it. They were poor but they never considered themselves deprived. They were always out on the streets, there were a lot of children about, communal action, a lot of politics, educational and cultural things going on. For the religious people there was all the religious stuff. There was a big mixture of everything. Their family and friends were still around. So my dad, while growing up, he’d bring me down every weekend to St-Laurent Boulevard, to introduce me to all his buddies who may have had stores there still. Cookie’s Main Lunch, on the corner of Marie-Anne and St-Laurent, he’d bring me there in the late 50s and early 60s. Where Bagel etc. is now. Little did he know I’d later take over the entire third floor of that building—my son was born there. Right above where the Playwright’s Workshop later was. I had that place for twelve or thirteen years.

Leonard Cohen was my neighbor, across the street. I used to sit with him in Portuguese park. We’d have our coffee and cigarettes there in the morning. I barely knew who he was. Around 83 or 84, he was writing Hallelujah. We would sit in the park in the morning, he’d be writing in his notebook and we’d be talking and having coffee. We’d actually both make our coffee in our own places and come back and sit in the park together. He would bum cigarettes from me, because he was always quitting smoking, he didn’t want to buy any. Sometimes we’d go into Bagel Etc., after Cookie’s closed, and sit with Gadd and Matina. Sometimes my wife would come down from upstairs in the building. Leonard would hang out, (Juan) Rodriguez was there. There was also a sculptor friend of Leonard’s, Morton Rosengarden, who lived nearby …

Anyhow, we’d talk about music, and Leonard came up to my place one time to see my work and he said, “Eric, you have to go to the head office.” And I said, “What do you mean, the head office?” He said, “The head office!” I said, “What the heck are you talking about,” He said “The head office is New York City, Erik, that’s what I did. I went to the head office and I made it from the head office. You gotta go there, you can’t stick around here.” And that was 84 or a little earlier.

I knew he was a songwriter, but I didn’t really know he was a real famous guy or anything. He was a guy who lived across the street.

LR: He had been going through a bit of a lull at that point. He had quite a burst of fame in the 60s and then again a bit in the mid 70s, but then there was a dry spell there.

ES: Yeah, well we just hung out and talked and nobody bothered him, nobody recognized him. Mind you, Montreal is known to be very much like that. You can be a star here and no one’s going to really go crazy around you. I don’t think Cohen or Rufus still have too much trouble around town.

People did move elsewhere and made more money, but the cost of living was so low in Montreal. I paid $75 a month in rent on St-Urban Street, between St-Viateur and Fairmount in 1975. And I lived with my girlfriend – so who couldn’t afford $75 a month. We didn’t have much money but it was only 37.50 each. That left us with enough money to go to cheap restaurants, shows for a couple bucks…

LR: And even though minimum wage must’ve been around $2 an hour, still…

ES: You were still making at least $75 a week, or a hundred.

LR: So it was barely a week’s work at minimum wage. It’s a lot more work for a month’s rent now, that’s for sure.

ES: Unless you share it with many people. So when we see the huge change in the Mile End in the past few years, a huge bunch of the influx is students. Many of them have their parents paying their rent while they’re in school. Many from France as well, and just about anywhere else you can think of – Winnipeg, Vancouver, Ontario, they all think this is the coolest place to live, but they don’t have an attachment to the place, no sense of history of this neighborhood. And they’re going to take off in two or three years as soon as they graduate and get a job in New York or Toronto.

LR: I presume there was some of that around McGill even back then.

ES: But the McGill Ghetto hasn’t been a community of consistent residents probably for 100 years. At some point before the University got really big there were probably a lot of families there. But Mile-End was always a consistent community of families that lived here. Those families are dying out, moving away, selling their properties for huge amounts of money. Their children have gone away, and who’s able to buy a house for a million dollars or whatever. It’s going to be somebody with a lot of money, who hears that this is the cool area.

LR: Like what happened to Greenwich Village in the 90s.

ES: Maybe. I lived in Greenwich Village in 77, 78. I loved it, it was terrific.

LR: What about the PQ coming to power in 76, a lot of English Montrealers we’ve spoken to said it was a turning point.

ES: I had my friends who took off to Toronto right after Rene Levesque won in 76. My girlfriend and I, at the time, loved the guy– he represented almost like a socialist future for this province. Like a caring, honest government. The night he won, we sat at a bar on St-Laurent near St-Viateur. Next to it was a steamed hot dog joint and a brasserie. We sat there watching election returns come in on TV, we were the only English-speaking people in the bar that night. When the Parti Québecois won, people went crazy, cars were honking down the street. Then all of a sudden, her and I felt a little bit nervous and uncomfortable. I had voted for him – she was American, she couldn’t vote. We just felt a bit uncomfortable – a lot of crazy things were being said, we just thought maybe there would end up being some crazy people out there. So we just went home after that. And later, a lot of my friends moved to Toronto. They’d arrange to continue University there, I forget what month it was, when the election happened. I was already out of their group, living in Mile-End while they were either still living with their parents or further in the suburbs. They all just kind of drifted off to Toronto or Vancouver and places like that. I had no reason to leave, I was happy here. My mother transferred ALL her money to Toronto. Emptied her bank accounts – not that it made any difference. It was just this fear from her past, that something bad might happen.

LR: It does sound like by the mid 70s the era that began with the mid 60s we started with was already ending. In Montreal with the Olympics, the PQ in 76, the disco explosion, it’s like just 7 or 8 years later the 60s must’ve felt like a distant memory.

ES: I think it came in with us, with my generation and went out with my generation. It came in with people my age starting say in the early 60’s, mid-60’s, influenced a lot from the American side and then a little bit later the political side through the European political scene in ’68 and ’69, and then as we gotten into our twenties and had to take on more adult responsibilities, now we are getting into the exact period you said, mid 70’s. We left it all behind: we had to leave the drugs behind because we had to get jobs or graduate from University, or at least do a lot less drugs. We had to earn money to pay our way unless we had very wealthy parents.

The people going to the disco clubs were not my people. I know they had these big clubs on Mountain street, and cocaine became the drug, and we didn’t do cocaine. We had pretty much come to the end of the drug thing because we had already been doing it for 10 years or 15 years. There were those who just went crazy and were dead already, and those who survived like myself. So the people going to the discos was a new kind of consumerism, kind of “let me show you how beautiful I am, see me, look at me, admire me, I want to be seen with this person, let’s do the cocaine and get this kind of super energy that we can dance and make love in the bathroom and not care and spend as much money as we can.” Show the cash, pick up the pretty girl or the handsome guy, it was so anathema to the hippie ideal of just freedom, peace and like, no money. It was completely the opposite — we just couldn’t get into that at all. It turned us off completely so we just went somewhere else.

LR: So all of a sudden, the sixties thing is firmly part of the past, something to be revisited. It’s not alive anymore.

ES: I don’t want to live in the past. I am not one of those guys that listens to radio stations that only plays 60’s music. No, I want to know what people are listening to. I enjoy that era, I am interested in it but I am not a fanatic about it. I just started the Facebook group for people to express themselves and have a little bit of amusement. Some guys are still at the Tam-Tams, you see guys my age who are still hippies, they got hair down to here, they are totally stoned out on acid, they are turning around in circles, I watch these guys and I think: wow, that would be me if I never had stopped doing LSD. That’s not where I want to live. I do totally respect the history, though, I love history and it is a part of history. But so it everything that is going on right now whether we like it or we don’t, and it’s better to know than not to know. Because if you know the history, then things make sense now. So the war in Iraq or Syria, whatever, doesn’t make sense unless you know the history of the Middle East, unless you know about colonialism and how it affected the face of Africa and the Middle East and then, suddenly it makes sense – oh I understand why these people hate each other, they never lived together before, they were in different places. So this is at a different level, but it holds as much importance in history of the city or the culture.

LR: So I guess the 60s are important in part for how we’ve moved on from it, not as a glorious perfect time – I mean some things were awful in the 60s, if we glorified it too much we’d be ignoring things like it maybe wasn’t as easy being gay or a woman in the 60’s, and maybe the whole free love thing wasn’t always the most pleasant thing for young women at the time. Things like pay equity were battles that came later.

ES: Yeah, and those are good advances. I am also very privileged to have been able to live through all of those different things.

– – –