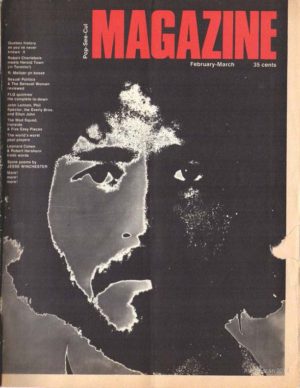

Juan Rodriguez Rock Journalist Legend and Pop See Cul zine

LR: That’s like the summer of ’66, isn’t it?

JR: Yup. It had The Lovin’ Spoonful on the cover.

LR: We got a copy from Francois Dallegret but it’s in rough shape. Is Andrew Cowan still around? Any of your old colleagues might still have copies?

JR: Andrew’s still around, he might have it. My mom might still have some in London.

LR: This one says number three, autumn ’66. What inspired you to put out your own magazine?

JR: Everybody else was doing it. At one point we were like a member of the Underground Press Syndicate. It just seemed very natural, that was the thing that I wanted to do. You may have noticed I have a bit of a stutter, and it was terrible as a kid. Absolutely terrible. They’d laugh at me, and I’m convinced that that’s what made me want to write. I always had something to say.

LR: This is more pop music than political…

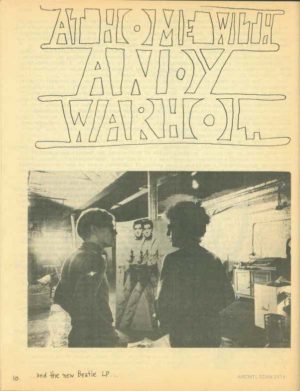

JR: But I liked to juxtapose pop type stuff with more serious stuff. We have an article by Buckminster Fuller… In this one you see Crawdaddy, which was the magazine of rock and roll started by Paul Williams, gave us one of Paul’s pieces in return for an ad. And then this here, I don’t know if you remember the hockey referee Red Storey? That was his son, Doug Storey. Doug was the odd guy out in the family, he was interested in music and all that stuff. And somehow he infiltrated himself with the Andy Warhol crowd.

AT: He didn’t take these pictures himself, did he?

JR: No, but they were lying around there and he picked them up, and there we go; “Exclusive!”

DD: Did you mention the other day that you found some of the Pop-see-cul content in an Andy Warhol Velvet Underground book?

JR: Yeah, the book that came out, I guess about two years ago. In the middle of it there was a copy of about six pages of Pop-see-cul, like a little collage, and Gary Eisenkraft had published that. It was funny because he promised us typesetting and managed to get a great deal from Monsieur Péladeau, because at that time, all Péladeau had was the Journal de Montréal, which had just started, because of strikes at Le Presse. So they were looking for business for the printing press. Gary printed four thousand of them and it was the biggest run that we ever had, huge, huge, huge. But unfortunately Gary wasn’t much of a distributor and they were left in a pile, most of them. We always went from store to store, you know, “Would you take this?”

LR: Metropolitan News?

JR: Yeah, Metropolitan News was the big one, but Classics Bookshop used to carry the Village Voice, and when we came out, they’d buy a whole pile. So anyway, he had these piles of magazines in his hallway. The apartment was on the third floor next to the Holt Renfrew building, where his girlfriend Melinda lived. They filmed The Ernie Game upstairs in that apartment, and there’s a scene, as you’re looking down the hall, and there they are.

AT: That’s why no one could find that copy, right? Because they’re all there.

JR: Yeah, it was a hoot. (Flipping through copies of Pop-see-cul): Here’s another article: Arthur Bardo was the art critic for the Montreal Star who moved here from New York. He was very rough on the art scene here, writing an article for Pop-see-cul called “Why High Art Never Got Off The Ground In Montreal.” That was him officially burning his bridges. There was also an open letter to Leonard Cohen by Robert Hirschhorn, who was a big publisher. Le Château was so upset about this ad here. Herschel Segal was the owner of Le Château and he supported the magazine. We actually had an office on Crescent Street, Sidney Rosenstone had a couple offices just above from where Ziggy’s is now. So we got this guy from New York who moved up to Montreal, Larry Schnitzer, and he was a very funny bonehead. We didn’t have any original art except for the Le Chateau logo, and so it was Larry who did this scrawl of the thing, and we went with it. Hershel was so angry.

LR: So he just didn’t like it, but then again, he told you to do whatever you wanted, didn’t he?

JR: Yup, he did. Then here’s Richard Meltzer, he’s famous for The Aesthetics of Rock.

LR: Did you republish this?

JR: No, that was an original article. Meltzer’s one of my greatest friends. Back in those days, you know, we had to lay the sheets out to collate them…

LR: Ah, we used to do that with my own zine Fish Piss from the 90’s, I think we were trying to do the same thing in different eras. Mixing politics with music and culture…

JR: Yeah, Fish Piss, oh wow, I read that…

AT: Did you ever see this magazine, Pop Cycle? I got this from Alain Simard, he told me the reason they chose this title, which was the first issue and only issue of this paper, was because of your paper Pop-See-Cul. And this was ’71, just when your magazine had basically come to an end.

JR: Isn’t that something, Pop Cycle.

AT: When he told me about that I said no, that can’t be right, he must be talking about Pop Rock Jeunesse…

JR: Well I did write a French article for Pop Rock, which was a tabloid like that, put out by Coco Jacques Letendre. He was a big music maniac, and I was able to get an exclusive music interview with Robbie Robertson. He had it in Pop Rock and I had my version in The Montreal Star. That was a whole story in itself. Robbie lived in the Côte-des-Neiges area, Jean Brillant Avenue, with his girlfriend Dominique. And he spent a winter here. We got together, she called me up at The Star and said that he wanted me to do an interview with him for a project that he had in mind. We went to this restaurant to talk about a movie on the Band’s roots and stuff like that. He wanted an article to help get Canadian funding for this movie, and they refused him. And that’s when he went to Hollywood for “The Last Waltz.” And Robbie, knowing that I had tried my best, invited me out to The Last Waltz for free. Everything was paid for by Capitol Records free of charge. I will always remember that concert which had everybody in it, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton, Joni Mitchell. I’d never seen so much cocaine in my life. It was just unbelievable. And you doubtless heard the story that Martin Scorsese had to rub out frame-by-frame a rock that was hanging from Neil Young’s nose. They had to do it by hand. And I remember going up the elevator with Eric Clapton, and Eric Clapton was just leaning up the elevator, just like that. It was terrific coke, by the way. It was fantastic. I remember Peter Goddard from the Toronto Star, we were the only two journalists there. I was in the room, you know, spread a little bit of coke down, and Peter had never tried it. He sniffs it up and then he goes “Ah-choo!” and there was coke flying everywhere … (Laughter). So that was the last time with Peter. At The Last Waltz I drifted up into the Cow Palace almost behind the stage, like looking down, and the only other person there was Michael J. Pollard from the movie “Bonnie and Clyde.” So we sat together, he had a little bit of weed, I had a little bit of coke, and we wordlessly did our thing, you know? And when Robbie saw me during rehearsal, I said “How’s everything going?” and he said “Well, it’s going pretty good, everything’s fitting nicely into the pocket.” (Laughs). That was the way he was. That was about the peak of the seventies. From my perspective, and I think I’m very correct in this, when The Beatles came, hit North America, the industry itself was not ready for it. They didn’t have enough pressing plants. They couldn’t handle the demand.

AT: You’re right, seems like whatever happened in the fifties did not grow the machine big enough, fast enough to accommodate the British Invasion.

JR: They kept hoisting out all the Bobbies on us: Bobby Vinton, Bobby Vee, all of them, and they had tried to arrest rock and roll, like they put Chuck Berry in jail, they had banished Jerry Lee Lewis because of the thirteen year old cousin. Fuck, who did the Beatles replace at number one? The Flying Nun. That’s what they foisted on us, you know? And so, boom! And then everything started accelerating very, very fast. We got the West Coast sound, we got the Boston sound, we had New York, The Velvets just got together, and it was in the seventies that the industry itself blew up into a monolith. And I think it was the age of the singer-songwriters, the first seeds of heavy rock, you know? And that’s what built the industry, like Carole King and all those people, one singer-songwriter after another, James Taylor, I couldn’t stand any of them. But it became a mega, mega, mega industry. And my friend Meltzer said basically rock and roll stopped in 1968. Everything after that was just hype and bullshit. And the hype machine was amazing. They used to buy journalists off. My first week on the job at The Star, I had written six freelance pieces for The Gazette, quite little pieces but I did the first Jesse Winchester article, that was the first time he was ever reviewed. After six had appeared, I finally called up the editor and said do you think I could get paid for this? And he said, “Oh okay, fifteen bucks a pop, chickenfeed.” That’s exactly the way; “Oh, thank you sir, thank you so much.”

DD: Now you’re a professional, right? When you get paid you’re a professional.

JR: Exactly. And then I decided to go to London in ’69, where the action was. I lived there for six months. At that time The Stones were getting rid of Brian Jones. I rang The Stones’ office and said “I’m here from The Montreal Star, can I do an interview with The Stones,” and they didn’t say no. The secretary said, “We’re going to have a major announcement coming up in a few weeks, let me put you on the list.” And sure enough, I was the international representative when they introduced and I went to their offices on Warder Street, and they introduced Mick Taylor, and that was the first time I interviewed The Stones.

AT: Did you know at the time that (Montreal singer) Nanette Workman was in London, that she had sang on “Honky-Tonk Woman”?

JR: And “Midnight Rambler” also.

AT: You were familiar that she had been in Montreal with Tony Roman and all those people?

JR: That’s right. I got to know Tony very, very well. What I said to The Star in March ’69 was “If I get you an interview with The Rolling Stones, will you hire me as a pop critic?” And they had no pop critic at that time. In hindsight, that’s when everybody started hiring a pop critic. When shows would happen they would get the theatre critic to write about it or the dance critic. And sure enough, I got hired in September of ’69. The first show that I reviewed was The Doors at The Forum and Jim Morrison was so fucking drunk that The Doors didn’t even stop between songs, they just kept rolling into the next one, get the show over with as quickly as possible. And I had to write the review, and the headline was “Doors Bore but Boppers Lap It Up.” Did I ever get mail!

AT: You must have received a lot of hate mail. I read reviews of Led Zeppelin, The Kinks, Bowie, and stuff, so, like those fans… The Kinks at the FC Smith auditorium in ’69 or ’70, and I was thinking, “That guy must have had a lot of enemies.”

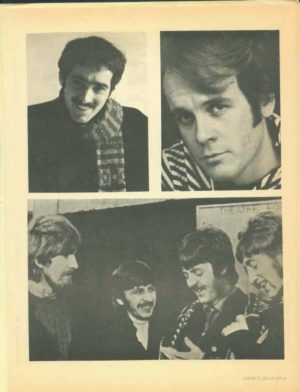

JR: It was great, I was the guy that they loved to hate. And it was the hype that got me riled up about The Kinks, because The Kinks, for me right now, I prefer their stuff more than any other British Invasion group, period. It transcends the word “classic,” it is rock and roll, you know? And their early hits were fantastic, and then Ray Davies, when he started writing the social stuff dedicated to all the fashion, stuff like that, nobody had even touched him, as far as zeroing in on class, and all this kind of stuff. That’s why I always thought that The Beatles were totally overrated and I still believe that to this day.

AT: They weren’t writing relevant songs to people?

JR: The Beatles were a phenomenon, and there’s a difference between music and a phenomenon. They were an incredible phenomenon, they were an incredible catalyst, you can’t say enough about them. But as far as songs were concerned, first of all, I loved their covers of Motown stuff, but songs like “Please Please Me,” and “Love Me Do,” weren’t very substantial songs. And I always thought “Sergeant Pepper” was a piece of shit, apart from one song; “Day in the Life,” which I thought was a masterpiece. And what I’m beginning to see now in the polls, “Sergeant Pepper” was always the number one album, it was de facto, and in the last issue of Uncut Magazine, they had the two-hundred greatest albums of all time and “Sergeant Pepper” had slid to number twenty-one. So it’s on its way down now. “Rubber Soul” was good too. I’ll always remember a rainy night in Montreal, it was November ’65 when “Rubber Soul” came out, eh? And I went to Archambault, because Archambault had the record store, in Place Ville Marie, and I bought “Rubber Soul” and I bought Ray Charles and Milt Jackson “Soul Meeting.” Jazz and pop. And I felt so proud of myself that I could like the both of them equally. “Rubber Soul” was a very sophisticated album and very good. But, you know, at that time The Stones did much better stuff, “Beggar’s Banquet,” “Let It Bleed,” those are fantastic albums. There were no throwaways at all.

Comments