Endre Farkas, Montrealer and Véhicule Poet

LR: It seems like cheap rents are a catalyst for a lot of these creative periods. In the early 70’s there seems to be an explosion a bit different from today, a lot of these things have turned into long-running institutions. Obviously Véhicule Press had its roots there and is very established, The Word is an institution of its own even though it is still small. It seems like the early 60s didn’t have much of that, just a few years earlier it would have been inconceivable to just grab this building and start doing readings.

EF: That was the hippie movement. It was lot more political on the francophone side, but on the English side it was more cultural.

LR: There was still a sense of taking charge of our own generation’s affairs, it doesn’t sound like you guys were looking to go to the big time, you seemed to be happy with where you were or at least comfortable.

EF: It was a different attitude. First of all, I am from the baby boomer generation. A whole bunch of us graduated or came of age around the same time, so that inevitably would have some effect. We were also influenced by the movements down in the States, anti-war and for peace and love, nice ideas to adopt. We didn’t have a war to resist, we offered sanctuary, so that made us good people. So the ideas of coops, the feminist movement, the collectives like the Véhicule Art Gallery seemed like a good alternatives to the hierarchical models. Also the fact that these baby boomer artists had no place to show works made it natural for us to start our own. Véhicule was the second or third alternative gallery to get started in Canada. It ran as a collective– everything was coming together on that shared basis, the commune, the collective, the coop, we worked together, as a possibility that the world could become this. We weren’t looking for careers.

LR: You were trying to build a sort of new way of living as artists?

EF: Yeah. That was all part of the game. We also saw as writers the shifting of the English literary culture to Toronto, and we didn’t want to go there or couldn’t afford to go there, and so we made the scene here. But here, we didn’t have the same kind of press, the same kind of PR, the same kind of drive to be national as they did in Toronto. In the late 60’s, early 70’s people like Atwood, Ondaatje started to emerge, the Toronto establishment pushed them, Northrop Frye spoke of them, and so they became Can-Lit and everyone else was on the margin.

LR: But she was in Montreal at McGill in the early 60’s, and was talked about as an up-and-coming female poet.

EF: That was when Dudek was publishing. Dudek wasn’t that crazy about her at the beginning, because he didn’t like that myth, epic style that Northern Frye was pushing, so there was that political, cultural literary war. Dudek just hated what Frye was doing, hated what Marshall McLuhan was doing.

LR: Really? McLuhan was a bit different, it was more intellectual I guess.

EF: Dudek was convinced that McLuhan was a charlatan.

LR: That he was just pandering to the hippies?

EF: Well, he was a one-phrase wonder, if anything.

LR: The medium is the message.

EF: That was one, and the “Global Village” was another. Dudek wrote quite a few articles against McLuhan. Canada also started to get a sense of identity, English Canada was looking to Toronto, and Toronto was saying: we are the centre. That’s where a lot of the resentment came from.

LR: Do you think some of that was sort of discomfort with the post-October crisis business, because you are talking before Lévesque takes over in 1976….

EF: Well, when the nationalist movement started in Quebec, I think it was a response, not a negative one from the literary world to say well we should also push our own literature, the English-language Canadian literature. There was a move to support that and so the development of the identity, the big thing in the 60’s and 70’s was: what is a Canadian?

LR: So you think maybe the French nationalism and their self-reflection influenced Canada to reflect as well.

EF: Yes, because Quebec was saying: we know who we are, who are you? And most of the literary response from the rest of Canada was silent sympathy. They understood and appreciated, and they somewhat envied the romantic nature of these artists being important to the cultural movement.

LR: So like all these events with Robert Charlebois, Gilles Vigneault…

EF: Yes, La Nuit de la Poésie.

LR: Crowds of tens of thousands and a sense of pride… that must have been impressive-looking given how I could imagine maybe some literary events in Toronto at the time would have been a little dull or a little less passionate.

EF: Yes, but they were also interesting. Coach House Press was really active and interesting, also House of Anansi started up. Talonbooks out West. So there was movement to create an interesting literary culture where you didn’t have to leave the country to make it. So once that shifted over there, the English-language writers in Quebec were left in a very strange, isolated position.

LR: Doubly isolated. Marginalized on both sides.

EF: Yeah, we were a minority within a minority. It was a refrain that was used a number of times, because we didn’t feel connected to the English ruling class that the French were objecting to.

LR: That didn’t mean you were fully sympathetic to their manner or intentions to separate?

EF: Some of us were. I voted yes in the first referendum. There were others like me. I could sympathize with them… by then I was familiar with the history and the idea of an independent state. I put it into the Letter to A.M. Klein that I also felt that if Quebec became independent, I would be in exile again.

LR: Was there a sense that it was a chance to start anew with a fresh country without the baggage of Canada, because having spent some time in a commune, I assume you were on the left side of the political spectrum.

EF: At that point, I was hanging out with separatist friends without any problems.

LR: Both English and French?

EF: Yeah. My French wasn’t good enough so often, unfortunately, when we had heated discussions, they would switch to English and I would try to say it in French but it was so difficult to explain the complexities of what I thought in French, so I said it in English and I responded in English: no, no speak in French! But I understood their desires. When it got to the point where some wanted to deny all rights to the English, that’s when I started to have trouble with it.

LR: So Bill 101 was a bit of a problem.

EF: Well, the thing about Bill 101 was, I still supported it because culture was exempt. In Bill 101, you could still make culture in whatever language you wanted to. I couldn’t care less if you had Eaton or Eaton’s, to me the sign law was absurd. To me, in my leftist view, Eaton’s was an exploiter on all levels anyway, so the apostrophic concern was ridiculous.

LR: What about the schooling? As an immigrant, had you immigrated in the late 70’s, you might not have been able to go to English school.

EF: These things were gradually giving me as a sense of feeling marginalized culturally, of being in a second-class position and to me that is scary. I had joined UNEQ, and they came out with a declaration that the literature of Quebec was French literature only. So I was a member of an organization dedicated to wiping me out!

LR: That’s where the nationalism becomes ethnic nationalism, especially someone from your provenance that has fled a situation where wasn’t tolerance.

EF: Exactly, and my parents being Holocaust survivors…

LR: So you changed your tune a bit between the first referendum and the later years …

EF: Yeah, I understood them, but I didn’t support them. And I thought that there was… I sent my kids to French school, they are fully bilingual, but even my daughter, who has no accent, said that there were times when because her name was Harwood-Farkas, as opposed to Desaulniers or whatever, that she knew she was excluded from certain things. So there was that feeling of being excluded.

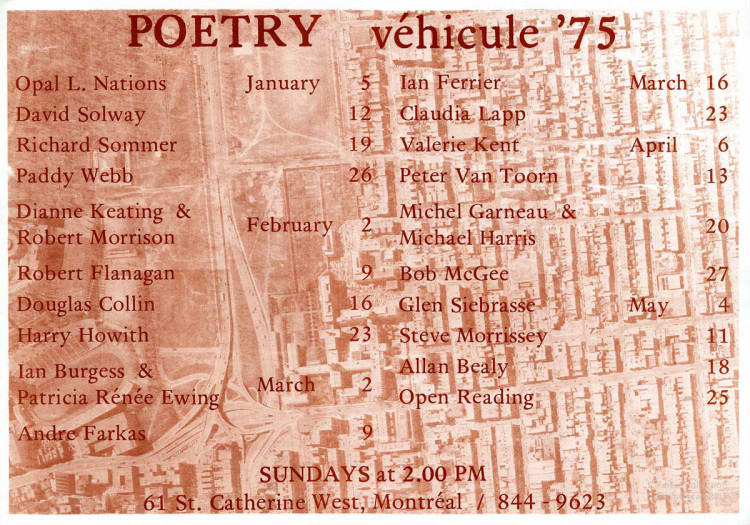

LF: Getting back to ’74-’75, Véhicule events, I am looking at some event calendars here and it’s all English. However, a little later on in the game there are people like Lucien Francoeur…

EF: Well Lucien was an interesting case. Lucien was of the generation that hated – well hated might be a strong word –didn’t agree with the nationalist movement. I mean, he loved all things American and most of the Lèvres urbaines – the Urban lips – that’s Claude Beausoleil, Claudine Bertrand a whole bunch of others including J.P. Daoust, these guys were very much American-influenced. They were still very strong French nationalists, but internationalists. I connected with Lucien and brought him into Véhicule for his translation. I was asked by Gaston Bellemare, who ran the Trois-Rivières Poésie festival, to organize English readings there. I started bringing in English writers, so they weren’t opposed to that, but people like Gaston Miron were very hesitant to becoming involved in any way, shape or form with the English. He didn’t trust them. These guys weren’t so afraid of that, they were confident enough in their own world by then. For me, the more mélange, the more goulash, the better. To me, bring on the mix. But the confidence, there is a growing pain to that confidence, and in the 70’s some Francophones maybe had to say “Fuck off, we are the maître chez nous” to build that confidence. Now they’re a lot less like that.

LR: It’s also such a different era, young people are exposed to the world online…

EF: Yes, and they look to the world as a possibility, whereas before, if you were from Quebec and a Francophone, you had to go to Paris and try to make it. Charlebois was booed off stage the first time he sang there because of the joual. Michel Tremblay, his plays were ridiculed because of the joual of Les Belles-Soeurs, and now he’s the darling.

LR: Somewhat similar in a way to say the 1950’s poetry and literary scene would use working-class English, or slang, or saying “yeah,” that must have been a similar liberation in the 70’s.

EF: Yes, taking it back from the academics.

LR: And from the heavy past.

EF: Yeah, and then in Canada there was also the other cultural battle of taking it back from the Americans, or protecting ourselves from the Americans and their influence. And then people like George Bowering were criticized for being influenced by the Black Mountain (North Carolina) poets, Poets like Robert Creely, Robert Duncan, Charles Olson, taught there. Even Irving Layton got criticized for being American, because it was sort of a break from the British influence, of Scott Smith and those guys.