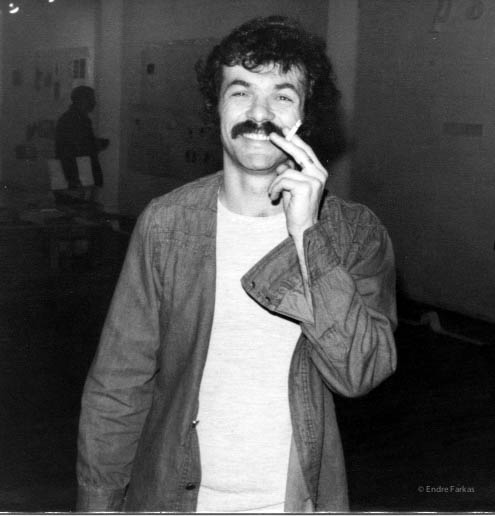

Endre Farkas, Montrealer and Véhicule Poet

Endre Farkas came to Montreal as a child after he and his parents (Holocaust survivors) escaped during the 1956 Hungarian uprising. He is a well-known and highly regarded figure in Montreal’s literary scene, coming to the city’s attention as one of the Véhicule poets—the group of poets who held regular poetry readings at the Véhicule Art artist-run gallery in the mid 1970s. He also taught literature at John Abbott College since the 1970s and has remained very active in writing, performing, editing and publishing poetry and literary works in the city and beyond.

Among his own eleven published books of poetry and plays, titles have been translated into French, Spanish, Italian, Slovenian and Turkish. He most recently edited (along with Carolyn Marie Souaid) Language Matters: Interviews with 22 Quebec Poets. He has read and performed widely internationally, and has innovated interdisciplinary pieces with musicians, actors, dancers and other poets live and on radio across Canada and Europe. His videopoem Blood is Blood, co-written/produced with Carolyn Marie Souaid, won first prize at the Berlin International Poetry Film Festival in 2012. His novel Never, Again will be published in 2016, and he is working on turning an early work, Murders in the Welcome Café, into a video-play.

After participating in our round-table discussion at the Blue Metropolis Festival in the spring of 2015 we met in the summer to speak about his school years and the development of his literary career in 1970s Montreal.

As with many of the people interviewed for this project, Endre had connected to the “underground” scene in Montreal as a student in the 1960s, taking in shows by bands such as the Fugs and Sidetrack at the New Penelope Café while not busy taking part in the occupation during the leadup to the infamous Sir George Affair at Sir George Williams University.

He grew up in the “St-Urbain” area (before it was commonly referred to as the Plateau or Mile End), on Park Avenue, on the west side between Fairmount and St-Viateur. With both parents working, he was what was then called a “latchkey kid”, going to school with a copy of the house key because he’d normally get home before his working parents did. He went to Baron Byng High School (where the Sun Youth charity is now located), where several of Montreal’s best-known Jewish writers such as Mordecai Richler had attended. He recalled playing in alleys after school to kill time before supper, or Mont-Royal or Fletcher’s Field (now Parc Jeanne-Mance) but certainly not Outremont Park (which is still somewhat restricted to its residents), or later on going to a pool hall on Clark St. near Rachel.

Unlike the post-Bill 101 era, Farkas explained that in his day, many immigrants of his generation ended up in English rather than in French schools for the main reason that French schools were restricted to Catholics, whereas just about anyone could enrol in a (free) Protestant school. Louis Rastelli spoke with him over the summer of 2015.

…

LR: Did you live in Mile End all through high school?

EF: No, in high school, by that time towards the end of high school, we had moved further up on the scale of success, we lived in Chomedey.

LR: That was one of the first places in the suburbs that Mile-Enders moved on to.

EF: And Park-Ex, Côte-St-Luc, Hampstead –the nouveau riche, sort of the new middle class moved to Chomedey. You could still buy a house with your salary. So I went to high school in Chomedey and was a jock, basically.

LR: I wouldn’t have guessed! And you became an accomplished poet later on.

EF: Well, I always loved soccer. But I connected – it was also the beginning of drugs – I connected with probably the smartest kid in school, in Chomedey High. He was brilliant, also he was 5’5’’ with a beard playing football. So he turned me on to the Beats, I started reading them a little bit but wasn’t sure what it was all about.

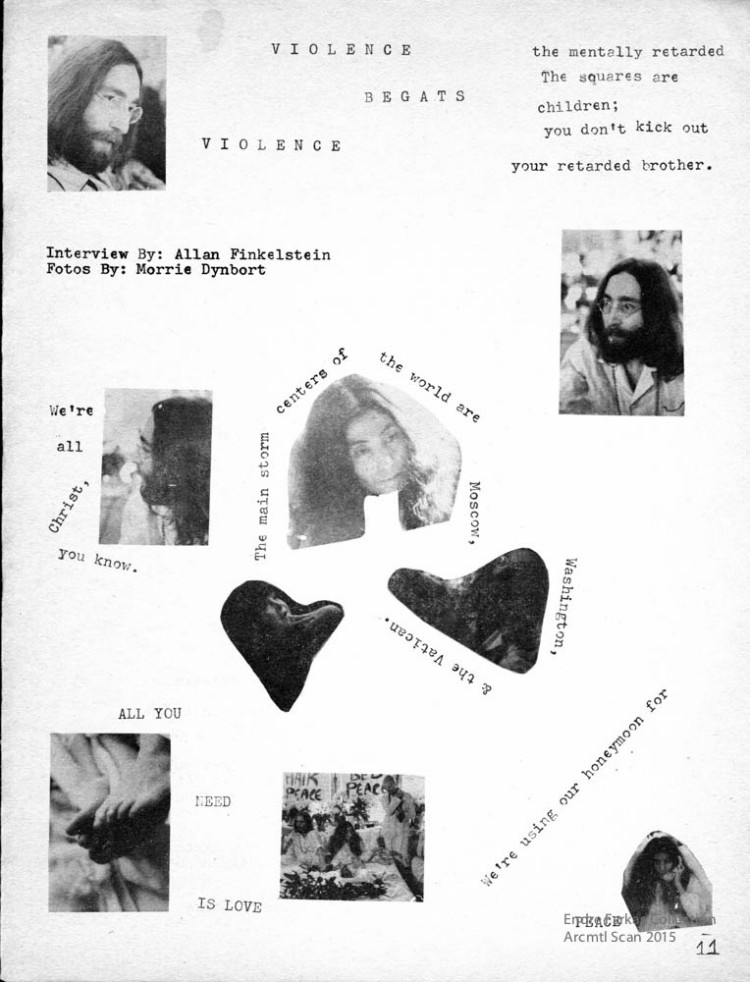

And then the grass and hash sort of came in. I was 16, 17. I tried it and started to like it, and one of the things that happened to me was that I started to listen to music and you started to read. Contrary to opinions of the time, I didn’t go insane and I didn’t kill anybody. I started reading, and he was writing his kind of Kerouac rambling prose, and we were listening to Dylan and to the later Beatles, the Doors, and started a literary magazine on our own. We put out about four issues. It was called The Ostrich. Our research showed that the ostrich, contrary to popular opinion, doesn’t stick its head in the ground when danger approaches. In fact it’s the creature that first senses trouble.

When I finished high school, I got a job because of my sports at The Gazette writing sports news. I was their “ethnic” reporter for soccer. Later I used my pass to go and interview John Lennon when he was here for the bed-in. I was there, but I left early, the night they recorded Give Peace A Chance, so I missed out on that. I could have been on that with my bad voice.

I had a picture of him that he signed, but I can’t find it.

From the zine Ostrich, a contribution in part by John Lennon while he was in Montreal for his sit-in.

LR: So you had already started writing in your last year of high school, and thanks to grass and hash, the guy was into the Beats so I guess you weren’t taught the Beats in any form in school at the time …

EF: Oh no. I don’t even know how Mark got hold of it, and Nietzsche.

Around 1966 when I started at Sir George University, in my Introduction to Canadian Literature consisted of a Mickey Mouse course taught by Michael Gnarowski, a friend of Louis Dudek’s. I was introduced to the work of Leonard Cohen, A.M. Klein, and Irving Layton. I said Hey! These guys are from my neighbourhood! it seemed to me that it was possible to be a writer in Montreal, especially if you are Jewish. (laughs)

LR: So that’s kind of odd– some people would say that there is a challenge to surmount there, but you saw an advantage, like “there is a niche here for me.”

EF: I just thought hey, they’re writing about the neighbourhood. Klein and Layton especially—it was an eye-opener.

LR: Especially after being force-fed Shakespeare and Victorian poetry.

EF: Yeah, and the Romantics and mainly American literature. At that time we had a lot of American professors because of the Vietnam War and draft-dodgers, but their attitude was that Canada had no literature. I remember one of them asking me: where’s your Hemingway, where’s your Faulkner?

LR: Oh boy. I know Canada was looked down at for navel-gazing and writing about itself, obsessing on identity.

EF: That came later. Most of the time it was colonial, the idea that how can Canada be interesting if you have to go to America or Britain to make it, That’s what Richler did and if you stayed here and wrote, you were a nobody. I had Richler as a teacher later on, he taught at Concordia. His teaching consisted of sitting around and chatting and taking us out for drinks after.